The root of a great dissertation is a robust research proposal. So, if you want to score highly on your dissertation, begin by writing a strong research proposal.

But how do you write a strong dissertation proposal? Well, find a topic that’s (a) interesting and (b) complements the existing literature. Then, narrow your focus until you can find a suitable dissertation title. Once you’ve got your title, choose an appropriate methodology, and check the overall feasibility of the project. Finally, structure your proposal clearly and succinctly.

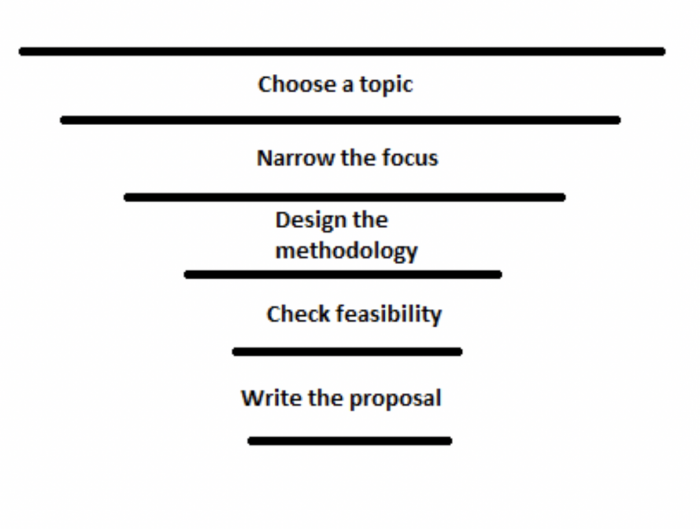

In many ways, writing a dissertation proposal is like pushing your ideas through a funnel. You’ll start with a very general idea and then filter this into a succinct proposal. That said, let’s explore the 5 stages of writing a dissertation proposal suggested by academics from our dissertation writing service.

What is a dissertation proposal?

In many ways, the dissertation proposal is similar to a Dragons’ den pitch. Although, instead of pitching a business opportunity to a den of dragons, you’ll be pitching a research strategy to a panel of academics.

The aim is to convince your faculty that the project is:

- Interesting

- Feasible

- Worthy of backing

Just like the entrepreneurs on Dragons’ den, you’ll need to be convincing. You’ll also need to demonstrate good background knowledge of the topic.

Thankfully, when it comes to pitching a dissertation, you won’t usually need to give a presentation. But you will have to write a robust research proposal.

How long should a dissertation proposal be?

Often, students worry about the length of their proposal. Is it too long? Is it too short? Well, it should be long enough to convey your idea, but short enough to remain concise. After all, concise writing is more convincing, because it shows that you understand the topic.

In practice, this means that dissertation proposals are typically between 750 and 2000 words. However, do check your university’s dissertation handbook for specific guidance.

Is the proposal the same as an essay plan?

If you can write an essay plan, then you should be able to write a dissertation proposal, right? Well, sort of. Although an essay plan is similar to a proposal, there is one key difference.

An essay plan synthesises your arguments in relation to an essay question set by your tutor. In contrast, a proposal is a strategy for a research project that you’ve chosen yourself.

A dissertation is more strategic than an essay plan because it requires you to pitch a new idea and then plan the entire research process from beginning-to-end.

So, instead of approaching your proposal as you would an essay plan, try to see it as a strategy or action plan, instead.

How should I structure it?

When structuring your proposal, try to think of it as a ‘mini-dissertation’. The proposal should include most of the sections that you’d find in a final dissertation, such as:

- Title

- Introduction

- Research background (a mini-literature review)

- Aims and objectives

- Methodology

- Limitations

- Timeline

- Draft conclusion

- References

If you structure your proposal like a ‘mini dissertation’, it’ll be much easier for your supervisor to understand. Also, if you’re not 100% sure how to write a dissertation, the proposal is a great opportunity to practise!

Where do I start?

Whichever way you look at it, the proposal can seem pretty daunting…

So, if you’re feeling overwhelmed by the dissertation proposal, what should you do? Where should you start?

Well, as with any other project, it’s best not to rush these things. A step-by-step approach will give you the time you need to develop a strong proposal. In fact, we think a 5-step funnel approach works best….

1. Come up with a topic

As you’d imagine, the first step is to choose a topic for your dissertation. At this stage, your ideas can be very general. In fact, you should try to be as open-minded and flexible as possible at this stage.

If you have a brain-block, then don’t worry. There are lots of ways you can generate ideas for dissertation topics:

- Ask yourself – What do I enjoy learning about? What area of study would complement my career goals? Which assignment did I score highest on?

- Visit the university library – Take out 5 books on topics that have interested you in the past and see if you can get inspired.

- Subscribe to a website/webzine – Choose one that’s relevant to your area of study. So, if you are studying Nursing, subscribe to BBC Health or Nursing Times. This will keep you up-to-date with topical news and relevant debates that could form the basis of your dissertation.

- Attend talks – Most universities host talks and events throughout the year. Try to sign-up to a few talks hosted by different faculties so you can get a flavour of what topics they’re interested in. After all, interdisciplinary dissertations can be really exciting.

- Look at past dissertations – Some universities make last year’s dissertations available on the intranet. Browsing through these can help, but make sure you don’t plagiarise.

- Down-time – Often, the most creative ideas come to us during periods of rest. Though, if we’re not careful, these ideas are quickly forgotten. So, if you get a sudden brain-wave whilst you’re down the gym or out with your friends, try to make a note of this so that you don’t forget it.

If you do all this, you should be able to come up with at least a few ideas for your dissertation. At this stage, it’s great to have more than one idea because some of them may not be feasible.

2. Narrow the focus

Once you’ve got a few topics in mind, it’s time to narrow the focus. At this stage, you’ll move from the general to the specific. This will help you to establish your research question(s) and proposal title.

But how do you narrow the focus? Well, you need to take your chosen topic and review the existing literature that’s been written on that topic. Remember, a dissertation should acknowledge the existing literature by:

- Corroborating it

- Challenging it

- Extending it/Filling a gap that’s missing

To ‘acknowledge’ the existing literature, you’ll need to have a firm understanding of it. So:

- Go to the library and take out handbooks/reference books that relate to your main topic. For example, if you’re interested in Green Marketing, choose books related to Marketing, Digital Marketing Strategy, Consumer Research, Environmental Marketing etc. In particular, look for books titled “Current debates in [your chosen topic]”.

- Visit Google Scholar or your university’s search tool and search for journals/books related to your keywords. Set the filter so that it only returns results from the last 10 years. Be creative with the search terms and try out different synonyms so that you don’t miss any relevant search results.

- If you are finding it hard to narrow the focus, speak to your lecturers for advice. Alternatively, our PhD specialists can provide guidance.

Once you have a rough title for your dissertation, you can move further down the funnel.

3. Design the methodology

Once you have your title, it’s time to choose your methodology. According to Abdulai (2014), choosing the right methodology will enhance the reliability and validity of your dissertation, so it’s really important to get it right. Here are some questions you should consider:

- Will I use deductive or inductive reasoning? If you’re searching for evidence to support/refute a specific hypothesis, this is deductive reasoning. In contrast, if your aims are very general – and it’s the findings of your study that will lead you towards a particular theory or paradigm – this is inductive reasoning. Generally speaking, deductive reasoning is most compatible with quantitative methods, whilst inductive reasoning is most compatible with qualitative methods. In order to design a robust methodology, you should be able to say whether you’re using deductive or inductive reasoning.

- Quantitative, qualitative or mixed-methods? It’s important to determine what type of data you’ll collect. As mentioned, this will partly depend on the type of reasoning you are using, as well as other factors. Some students opt for qualitative data analysis because they think it will be ‘easier’, but this is a fallacy; all methods can be equally challenging. So, choose the methodology that’s best suited to your research topic rather than the one you think will be easiest.

- Primary or secondary (or both)? Primary data is data you collect yourself – typically through surveys, questionnaires or interviews. Secondary data, on the other hand, is data that already exists, such as newspaper articles or data-sets from other researchers. Some methodologies combine both primary and secondary data collection (e.g. Exploratory case studies). Make sure you know what type of data you’ll be collecting so you can plan your time effectively.

4. Check if it’s feasible

Feasibility (or lack thereof) is main reason why dissertation topics are abandoned. Don’t wait until the last minute to check if your project is feasible or not. Ask yourself:

- Can it be completed in the time frame? – Generally speaking, students are advised to complete their dissertation over a 6 month period (this includes planning, research and writing). This might seem like a long time, but time really flies, especially when you have multiple assignments due at once. So, check whether you’ll have enough time to complete the project.

- Will it be approved by the University’s Ethics board? All dissertations will need to be approved by an Ethics board. Ethics is quite a complicated area so you should set aside some time to do some wider reading. However, a good place to start is to ask yourself: How would I access the participants? Would they face any risks to their mental/physical health by participating in my study? To increase validity, would I need to hide the aims of the research from participants? If so, what impact could deception have upon them?

- Would a professor from the department be willing/able to supervise this project? If you are unsure, you could ask your personal tutor or module leader for advice.

If the answer is an outright “no” to any of these questions, abandon the idea and move onto the next. But, if you think your idea could be feasible, it’s time to start writing the proposal!

5. Write the proposal

Producing a dissertation proposal is as much about research and refinement as it is about writing. So, writing the proposal is the last stage of the process. Remember, most of the proposal should be written in the future tense rather than the past tense because it’s a strategy document.

Start by creating the proposal structure in Word and then fill in the blanks. Often, it’s easiest to write the Research Background, Aims and Objectives, and Methodology first. The introduction will probably be written last.

Importantly, you should spend plenty of time on your Timeline. Break down your strategy into weekly goals so that you can monitor your progress. After all, if you don’t manage your time effectively, it’s very unlikely that you’ll achieve a high grade on your dissertation.

“Time is the scarcest resource and unless its managed, nothing else can be managed.”

– Peter Drucker

Once that’s complete, you’ll be ready to hand in your proposal! Though, remember, this probably won’t be the end of the refinement process. After seeing your supervisor, you may need to modify some elements of your proposal…

Is the proposal really necessary, then?

The direction of your dissertation may change after you’ve met your supervisor. But that’s no excuse to submit a half-hearted proposal! You should still put 100% effort into writing your proposal.

Whilst it’s true that dissertations do evolve as a result of supervision, they do not change completely.

Indeed, when marking a set of dissertations, it’s clear to see which are rooted in a robust research proposal and which are not.