Discuss the typical human responses to change and identify how these can be addressed by organisations seeking to undertake change

The only certainty in our present world is rapid and accelerating change. We can either ride with the changes hoping for the best or use the changes we recognise around us to our best advantage (CD-ROM 2005). In today’s complex business world of rapid technological innovation and globalisation, organisational need for rapid change is leading to different competitive pressures and human responses. These limit an organisation’s ability to grow and successfully implement the change process (Burnes 2000). This essay will examine the typical human responses to change generally and how organisations can address these reactions by evaluating the causes of human reactions and the behaviours exhibited. It will also discuss the benefits and limitations of different approaches which can be used to help individuals adjust to the change.

The most distinctive human response to any major or minor change is resistance. There are various causes and types of resistance to change, particularly at the organisational level. Individuals resist change as they fear letting go of the old, safe, routine ways of conducting their business for an unknown and unsafe territory. As humans, we prefer routines and tend to stick to our habits. But fear of change may be attributed to the possibility of failure, the relinquishing or diminishing of one’s span of control and authority or that the planned change has little or no effect on the organisation whatsoever. People may need time to integrate and get comfortable with the change. Any one of these possibilities can cause doubt and thus fear, understandably causing resistance to the change efforts (Change 2005).

Furthermore, the transition between the present state and the changed state is difficult for individuals and organisations, as it involves the ending of the current state. Endings must be acknowledged and managed before individuals can fully embrace the change. Even if the change is desired a sense of loss occurs as change redefines our roles, responsibilities, and context, which is not an easy process (Change 2005). William Bridges (1980) discusses the process of individual change by presenting four stages that individuals must pass through to move into the transition state and effectively change: disengagement, disidentification, disorientation and disenchantment.

The first stage of disengagement involves breaking with the old organisational practices and behaviours. Typical human responses exhibited will be refusal to engage with the change process, running away, quitting, seeking a transfer or taking early retirement, absenteeism and withdrawal of interest (Opie 2001). Table 1 shows the behaviours, typical responses and helping strategies to deal with disengaged people.

| Table 1 DISENGAGEMENT | ||

Typical Behaviours | Typical Verbal Responses | Helping Strategies |

| Loss of interest, drive and initiative. Low profile – unwilling to accept responsibility related to the change. Unresponsive – unwilling to ask questions. Doing the minimum to get by. Unwilling to seek out information. | No problem. I don’t care. It’s Okay. Anything you say.It doesn’t concern me. | Confront them with their behaviour – but do so descriptively rather than judgementally.Get them talking – be supportive and encouraging, listen. |

| Source: Opie 2001 | ||

After making the break, individuals need to be more flexible and recognise that they are not who they were before (Change 2005). This is the second stage of disidentification in which individuals tend to hang onto the past and have a distorted view of the future. This takes place when the individual’s values and something he identifies with are removed e.g. specific tasks, location, team, expertise and there seems to be nothing equivalent to replace it (Opie 2001) .The behaviours, verbal responses and helping strategies for disidentified people are illustrated in table 2.

| Table 2 DISIDENTIFICATION | ||

Typical Behaviours | Typical Verbal Responses | Helping Strategies |

| Dwelling on the past.Associating mainly with old colleagues or in old locations.Continuing to do the old job or use old methods. | I used to be……..It’ll never work.What was wrong with the old way? | Get them to talk about what they like about the ‘old’ way in a fairly precise way.Ask questions about how this might be carried forward into the new order – this seems to work better than telling. |

| Source: Opie 2001 | ||

Disenchantment, is the third stage of individual change in which individuals further clear away the “old,” challenge assumptions and create a deeper sense of reality for themselves by recognising that what once was is no more, something which they once valued has been taken away. Disenchantment is often associated with anger, which is easier to deal with when expressed directly and if suppressed may come out in more indirect ways (Opie 2001). Table 3 shows the typical behaviours, verbal responses and strategies which can be used to identify and deal with disenchanted individuals.

| Table 3 DISENCHANTMENT | ||

Typical Behaviours | Typical Verbal Responses | Helping Strategies |

| Sarcasm Back stabbing Self pity Sabotage Raised voice | Yes, but….You’ll/they’ll be sorry. It will never work. It’s stupid. It’s not fair. | Let them get it off their chest. Be supportive and accepting. Ask “why do you think that might be…?” Explore feelings in supportive way |

| Source: Opie 2001 | ||

In the fourth stage of individual change, disorientation individuals feel lost and confused. This is a very necessary but unpleasant state as individuals move into the transition state and to a new beginning. Disoriented people lose sight of where they fit in and what they should be doing and have trouble making sense of the new order of things. (Opie 2001). The behaviours, responses and strategies to help disoriented people are illustrated in table 4.

| Table 4 DISORIENTATION | ||

Typical Behaviours | Typical Verbal Responses | Helping Strategies |

| Asking questions – often going back over old ground. No action until questions answered. Cannot work out priorities. Information and detail focused. Encourages others to seek information on their behalf. | What do I do?Yes, but how will it work?Why are we doing this? | Provide information.Provide some reference points; deadlines, plans, early actions. Address the underlying issues by gently confronting the person. |

| Source: Opie 2001 | ||

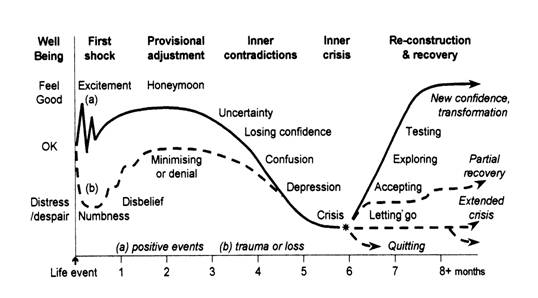

The reactions to change described above are typical human responses during uncertainty and change. However, as every individual is unique, he/she may react differently to the same change. Change is stressful for everyone and individuals go through several stages to fully adapt to it. These stages are shown in table 5.

Table 5 The transition cycle – a template for human responses to change

Source: Williams (2001)

It can be seen from table 5 that individuals respond to change by making radical changes in their values and attitudes as appropriate to their new environment. If change is effectively understood and supported it can be a turning point and opportunity and if not; it can lead to serious errors of judgement, depression, breakdown, broken relationships and careers, and sometimes suicide (Williams 2001).

It is easier to overcome resistance to change if we are able to control the change (e.g. marriage, new home) than when we have little or no control (e.g. new job, responsibilities, job relocation) over it (Change 2005). There are a number of approaches which can be adopted by organisations to motivate employees and overcome resistance as discussed below.

Companies need to create a readiness for change amongt their employees by adopting an approach that is aware of the possibility and causes of resistance and deals with these at an early stage. Organisations such as Oticon and Flair have made and continue to make efforts in creating a climate where change is accepted as the norm. Organisations can achieve this by informing their employees on a regular basis about its vision, strategic plan for the future, the competitive market pressures it faces, customers requirements and the performance of its competitors. This approach makes members of the organisation appreciate that change is inevitable and is being undertaken to safeguard rather than threaten their future. Organisations must recognise that change creates uncertainty, resistance among individuals and groups and they may not fully co-operate with it if they fear the consequences (Burnes 2000).

‘Education and delegation involves convincing employees of the need for change through means such as training, gaining their commitment and support for change and then delegating change to them’(Balogun ,Hope 1999 p.31). According to Zaltman and Duncan (1979) educative strategies provide a relatively unbiased presentation of the facts and a rational justification for action by assuming that organisational members and stakeholders are rational beings capable of discerning fact and adjusting their behavior when the facts are presented to them. This approach provides employees with an understanding and encourages them to use their learning to propose and implement change projects supportive of the organisational change goals. However, it is difficult to generate commitment and action from employees as change will only occur if a series of explicit actions are identified and carried out. It can be very time consuming and expensive if a large number of employees need to be convinced (Balogun, Hope 1999).

Persuasive strategies can be used to motivate people to change by biasing the message to increase its appeal e.g. most advertising is persuasive in nature. Persuasive strategies are likely to be more effective than educative strategies when the level of commitment to change is low as they stress either realistically or falsely on the benefits of changing or the costs of not changing (Hayes 2002).

The participation, support and involvement of those who are most closely affected by change in the collection, analysis and presentation of information is of utmost importance as they are more likely to believe information they collect themselves than information presented to them by experts. Participation and involvement can ‘excite, motivate and help create a shared perception of the need for change within a target group’ (Hayes 2002 p. 140). This requires the concerned people to take ownership of the project so that it is “their” project and “their” success. Achieving this is difficult unless people can be involved in the planning and execution of the project. This type of involvement can be achieved by establishing an effective communication system which informs those affected by change from the beginning about what is happening, how it will affect them and will give them reports on the progress being made (Burnes 2000).

The benefits achieved are that the change management team quickly detects any worries and concerns, responds to these and becomes aware of other aspects that also need to be considered. Communication helps overcome fears, assists those undertaking change and involves them in the change process which is imperative for successful implementation of any change project (Burnes 2000). However, this approach can be a very time-consuming way of delivering change and if those involved have less technical expertise than the change initiators, it can result in a change plan that is not as good as it might be (Hayes 2002).

Individual responses to change can be tackled by building the enthusiasm and sustaining the momentum for change. To accomplish this, organisations need to be aware of and should identify and allocate any additional resources (financial and human) such as the provision of extra staff and the training of existing staff which are needed to achieve the change (Burnes 2000). According to Buchanan and Boddy (1992) just as the change management team is responsible for planning, supervising the change project, motivating staff and dealing with difficulties, they too need support otherwise they will become demoralised and lose their ability to motivate others.

Resistance caused by fear and anxiety can be overcome by offering facilitation and support by training in skills, giving time off after a demanding period or simply listening and providing emotional support. Organisations need to consider the new competencies and skills required by the change, who requires it and how to deliver it in a way that encourages rather than threatens employees (Burnes 2000).

Rewarding and reinforcing desired behavior helps participants develop a positive attitude about the change project. Kotter and Schlesinger (1979) suggest that negotiated agreements can avoid resistance when it is clear that those with sufficient power to resist change will lose out if the change is implemented. The problem, however, is that those contented with the change may see this as a possibility of improving their position through negotiation. (Hayes 2002).

Manipulation involves deliberately biasing messages to influence others to change. It also involves co-option. According to Kotter and Schlesinger (1979) co-opting gives an individual or a group a desirable role thereby securing their endorsement in the design or implementation of the change. This approach is quicker and cheaper than negotiation but it gives those who are co-opted the feeling of being “tricked” into supporting the change, they may exercise more influence than anticipated and steer the change in a direction not desired by the change initiators (Hayes 2002).

Direction is the ability to exercise the power to make the decisions about what and how to change and to use the authority to direct the achievement of change. Although this approach makes it easier to control the direction and content of change and decision-making is faster than it would be under an approach which involves consultation, the lack of employee consultation and involvement might create more resistance to the proposed changes and staff may find it easier to repeat the language of change process without really embracing the change at an emotional or behavioral level (Balogun and Hope 1999).

In conclusion, it can be said that change is inevitable and mastering it is fundamental to the success of an organisation. There are patterns of human responses generally to change that can be identified as ‘typical’. However, not everyone reacts ‘typically’ as people are individuals and can respond in their own unique way to situations. Organisations need to choose the most appropriate approach / approaches which match its change objectives and context by considering their benefits and limitations to create an environment in which individuals can learn and develop themselves. However, organisations need to make greater efforts to understand how their workforce will react to change, understand the nature of change and the best way to manage it, keeping in mind their organisational culture and values.

REFERENCES

Balogun J. & Hope Hailey V. (1999) Exploring Strategic Change. Harlow: Financial Times/Prentice Hall.

Bridges, W. (1980). Transitions: Making sense of life’s changes. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Buchanan, DA and Boddy, D. (1992) The expertise of the Change Agent: Prentice Hall: London.

Burnes B. (2000) Managing Change: A Strategic Approach to Organisational Dynamics

(3rd Edition). Harlow: Financial Times/Prentice Hall.

Change (2005) Organizational Change and Development [online]

http://64.233.183.104/search?q=cache:rwwekuuVs0IJ:jeritt.msu.edu/documents/TallmanWithoutAttachment.pdf+causes+of+disengagement,+disidentification,+disorientation,+disenchantment+&hl=en [15/02/2005].

CR-ROM (Change 2005) Management of Change, University of Bradford.

Hayes J. (2002) The Theory and Practice of Change Management. Basingstoke:

Palgrave.

Kotter, J.P. and Schlesinger, L.A. (1979) Choosing Strategies for Change, Harvard

Business Review, March/April.

Opie, M. (2001) Managing Change [online]

http://www.abersychan.demon.co.uk/hpt/change/managing_change.htm#DISORIENTATION [accessed 28/02/2005].

Williams, D. (2001) Transitions: managing personal and organisational change [online]

http://www.eoslifework.co.uk/futures.htm [accessed 25/02/2005].

Zaltman, G. and Duncan R. (1979) Strategies for Planned Change, CH 3, Resistance to

Change, London: John Wiley.