Here comes the Bogeyman – How certain Bogeymen were used to terrify the population in Victorian England.

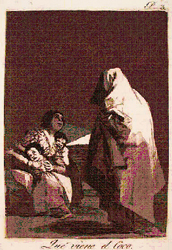

This etching by Goya, completed around 1800, was inscribed by the artist “Here comes the Bogeyman.” (‘Que viene el Coco’) It is a disturbing image in many respects as the mother cowers with her two children as the cowled figure approaches them; he surely means no good. (*) This hooded figure in the nineteenth century mind may well have come to encompass the mystery fear behind the unknown killer that was ‘The Ripper’ or the figure of terror that was seen as ‘Spring Heeled Jack.’ Much of this terror was inspired by the newspapers and had its links in earlier tales of terror with common threads across cultures.* Image : ‘Los Caprichos, by Goya, 1799, Image from the Davison online art centre. http://www.wesleyan.edu/dac/imag/1946/00D1/0040/1946-D1-40-0003-m01.html

This etching by Goya, completed around 1800, was inscribed by the artist “Here comes the Bogeyman.” (‘Que viene el Coco’) It is a disturbing image in many respects as the mother cowers with her two children as the cowled figure approaches them; he surely means no good. (*) This hooded figure in the nineteenth century mind may well have come to encompass the mystery fear behind the unknown killer that was ‘The Ripper’ or the figure of terror that was seen as ‘Spring Heeled Jack.’ Much of this terror was inspired by the newspapers and had its links in earlier tales of terror with common threads across cultures.* Image : ‘Los Caprichos, by Goya, 1799, Image from the Davison online art centre. http://www.wesleyan.edu/dac/imag/1946/00D1/0040/1946-D1-40-0003-m01.html

What this chapter will address is how certain ‘bogeymen’ were used to terrify the population, perhaps as ‘inventions’ or ‘elaborations’ of the press, but they satisfied the readers’ desire to be caught up in the atrociousness of acts as extreme as cannibalism. The stories used the fears of the reader and exemplified those half-formed qualms developing into anti-Semitism or mass hysteria. Marina Warner linked the ideas held in the Russian witch stories of ‘Baba Yaga’ with that of ‘Hansel and Gretel.’ (Warner, 1999, 26) Both characters prey on the young, although ‘Baba Yaga’ is not always malevolent and can be a ‘wise woman’ capable of great cruelty to those that cross her. Much of this is wrapped up with the ‘need’ for cruelty to be present in society, albeit at a distance. The Victorians would watch ‘Mr Punch’ a cruel baby basher and wife beater and laugh at his antics.

They would read about ‘The Sandman’ who in E.T.A. Hoffman’s (1817) Fairy Tale would “come to little children when they won’t go to bed and throws handfuls of sand in their eyes, so that they jump out of their heads all bloody…” (Hoffman, 1999, 32) The ‘Sandman’ here is a fairy tale tool to frighten the children to go to bed, in a way that “be good or Santa won’t come” may be used to make children behave. This Victorian advertising card for ‘Woolson Spice’ advertising (1891) shows the children waiting for Santa as the Sandman approaches; at least one of the children however is seen to be nervously awake. (*) Does the Sandman slip into witches garb here in the way that the ‘wicked witch’ can appear to children in the fairy tales? The idea of a threat to children if they don’t go to sleep is seen across cultures, a Spanish lullaby goes “Go to sleep, evening star, for here comes the bogeyman, and he steals away children who don’t go to sleep.” (Traditional)* Image: ‘The Coming of the Sandman as children wait for Santa’ comes from Woolson Spice Advertising, 1891, and is taken from ‘Acclaim Images,’ http://www.acclaimimages.com/_gallery/_print_pages/0040-0409-0422-0045.html

They would read about ‘The Sandman’ who in E.T.A. Hoffman’s (1817) Fairy Tale would “come to little children when they won’t go to bed and throws handfuls of sand in their eyes, so that they jump out of their heads all bloody…” (Hoffman, 1999, 32) The ‘Sandman’ here is a fairy tale tool to frighten the children to go to bed, in a way that “be good or Santa won’t come” may be used to make children behave. This Victorian advertising card for ‘Woolson Spice’ advertising (1891) shows the children waiting for Santa as the Sandman approaches; at least one of the children however is seen to be nervously awake. (*) Does the Sandman slip into witches garb here in the way that the ‘wicked witch’ can appear to children in the fairy tales? The idea of a threat to children if they don’t go to sleep is seen across cultures, a Spanish lullaby goes “Go to sleep, evening star, for here comes the bogeyman, and he steals away children who don’t go to sleep.” (Traditional)* Image: ‘The Coming of the Sandman as children wait for Santa’ comes from Woolson Spice Advertising, 1891, and is taken from ‘Acclaim Images,’ http://www.acclaimimages.com/_gallery/_print_pages/0040-0409-0422-0045.html

The idea that children or women require protection is a central idea behind the reporting of many Victorian ‘crimes’ and this chapter will explore reaction to ‘crimes’ such as the murder of ‘Sweet Fanny Adams, the notion of elements of ‘protecting women and children’, as well as the anti-Semitism and cannibalism within ‘The Ripper’ Case.

With regard to children, the nineteenth century had a complex view of childhood that is very different to that held today. Matthew Sweet notes this era as one in which ‘there was ‘sentimental adoration eroticism around childhood, at the same time enjoying the fruits of child labour.’ (Sweet, 2001, 166) The 1848 tale of ‘The Little Match Girl’ by Hans Christian Anderson shows how the girl is abused by her father and not allowed to go home unless she sells her matches. The imagery surrounding the tale often presents her as both vulnerable and alone, the image of childhood as one wrecked by the world around her. This type of image is reflected in the photography of the late Victorian era. This is a photograph of Alice Liddell, better known as ‘Alice in Wonderland;’ the inspiration for the book of that name and photographed here by the Rev. Charles Dodgson (Lewis Carroll). (*) The photograph entitled ‘The little beggar girl’ captures much of the fascination with the world of the fairies referred to in Chapter Two. There is also something about the picture that echoes similar period images of, for example, ‘The little match girl.’ It certainly belongs to the fairy tale world conjured up by Carroll in the Wonderland Tales where dream became reality, and holds an idea that within childhood we are closer to the world of nature and the unexplained.* Photograph entitled “the Little Beggar Girl” taken from: Glenn, J, ‘Defending Lewis Carroll,’ The Boston Globe, May 16th 2004, on line edition: http://www.boston.com/news/globe/ideas/articles/2004/05/16/defending_lewis_carroll/

With regard to children, the nineteenth century had a complex view of childhood that is very different to that held today. Matthew Sweet notes this era as one in which ‘there was ‘sentimental adoration eroticism around childhood, at the same time enjoying the fruits of child labour.’ (Sweet, 2001, 166) The 1848 tale of ‘The Little Match Girl’ by Hans Christian Anderson shows how the girl is abused by her father and not allowed to go home unless she sells her matches. The imagery surrounding the tale often presents her as both vulnerable and alone, the image of childhood as one wrecked by the world around her. This type of image is reflected in the photography of the late Victorian era. This is a photograph of Alice Liddell, better known as ‘Alice in Wonderland;’ the inspiration for the book of that name and photographed here by the Rev. Charles Dodgson (Lewis Carroll). (*) The photograph entitled ‘The little beggar girl’ captures much of the fascination with the world of the fairies referred to in Chapter Two. There is also something about the picture that echoes similar period images of, for example, ‘The little match girl.’ It certainly belongs to the fairy tale world conjured up by Carroll in the Wonderland Tales where dream became reality, and holds an idea that within childhood we are closer to the world of nature and the unexplained.* Photograph entitled “the Little Beggar Girl” taken from: Glenn, J, ‘Defending Lewis Carroll,’ The Boston Globe, May 16th 2004, on line edition: http://www.boston.com/news/globe/ideas/articles/2004/05/16/defending_lewis_carroll/

High profile cases of child murder, such as the ‘Huntley’ killings in recent years, has led to a media perception that such brutality is a ‘modern disease’ perhaps caused by an ‘addiction’ to horror films or to ‘18’ certificate ‘gore’ movies. Any research quickly shows that not to be the case. The murder, at Alton, of ‘Sweet’ Fanny Adams, aged eight, took place at Flood Meadow, on Saturday, August 24th, 1867. To add to the horror, the victim had been decapitated and brutally mutilated; the head fully decapitated and body parts spread over a wide area. By any standards this was a horrific murder. The murderer, Frederick Baker, 29, was arrested within hours with bloodstained clothing, Damning evidence was an entry in his diary, “killed a young girl;” he was hung in front of a crowd of nearly 5,000. The significance of the case is that it represented a violation of childhood, a story that “offered such an affecting mixture of pathos, atrocity, sadism and moral outrage that it established a vocabulary of popular sentiment in whose terms responses to violent crimes upon children have been articulated ever since.” (Sweet, 2001, 163) Perhaps from this point onwards parents were scared of letting their children out to play, and ‘beware of strangers’ became advice echoed across the land. The stranger, the ‘outsider’ could quickly become ‘the Jew’ or the ‘foreigner’ when the Victorians were under the mass fear caused by reports during the ‘Ripper’ killings.

In the midst of the Ripper killings the strange writing ‘The Juwes are the men that will not be blamed for nothing’ was found scrawled on a wall. Whitechapel had seen an influx of Russian Jews in the 1880’s and with it had come a form of anti-Semitism we would recognise today.

Whether this was actually written by the Ripper or not, its significance was such that it was seemingly rubbed off the wall before it was photographed. This officially was to protect the Jewish community, but it led to many anti-Jewish riots in the Whitechapel district. Jewish immigration into England had considerably increased and they were an often persecuted minority held to blame for much that was wrong in society. Leslie Fielder in his 1949 essay wrote ‘What can we do about Fagin’? “He (the Jew) is the Usurer, the Jew with the knife, the Jew as Beast. A compulsive image, he haunts the English imagination, a creature of fear and guilt, he exists before and beneath written literature…” (Davison, 2004, 23) With this context is it any wonder that the ‘Ripper’ case threw up all the latent prejudices within English society, the fear of the foreigner and suspicion of the Jew? The community of Jews in London, made up of a mixture of Polish, Russian, German and English heritage Jews, were represented through the Jewish Chronicle, and this publication expressed the fears of the community through the ‘Ripper’ period. There was competition in the area for housing and work and fears that immigration was too large. “Europe could be undermined by growing immigrant communities with little allegiance to their host countries,” (Almond, 2006, 1)) wrote a leader in ‘The Times’, not in 1888 but in 2006, showing sentiment does not often change over time, but re-manifests itself in times of tension. Familiar fears of the foreigner remain strong, fear of their motives and what they represent. We are presently in a time of war and in 1888 the threat was of something lurking within society that was inherently evil. Finzi wrote that “an antagonistic enemy within, like the Jew, was a pre-requisite for fostering nationalistic sentiment.” (Davison, 2004, 16) In the ‘Ripper’ case, the writing on the wall coupled with speculation that the ‘Ripper’ was an Israelite who had been intimate with a Christian woman, might be a butcher and possibly used the knives used by Jewish ‘kosher’ butchers, was enough to spur some papers into leading with anti-Jewish sentiment. ‘The Times’ had reported “passages quoted from the Talmud show that a belief existed among ignorant Jews that any Jew who had been intimate with a Christian woman could make an atonement by slaying and mutilating her.” (Jewish Chronicle, 05/10/1888) This stated…‘is forced to take issue at this slur which it felt endangered manyJewish Chronicle’ of their community in the East End. The October 1888 article refutes any existence of such a barbaric practice in any Jewish literature and suggests this lie has been made to inflame tension and look for a ‘scapegoat.’ It writes “although it is a Jewish Member of Parliament who offered the first reward for the discovery of the murderer, and Jews are active members of the Vigilance Committee, no one knows what an exited mob is capable of believing against any class which differs from the mob-majority by well-marked peculiarities.” (12) That essentially is the lie behind the bogeyman; he exists in people’s fears, the fear of any group that is different from the ‘mob majority.’

The ultimate taboo could well be cannibalism, it disgusts as much as any ‘crime’ and it appears under the surface of the reporting on the ‘Ripper’ and of ‘Katy Webster’ in the previous chapter. Predators fill our stories and imaginations from the earliest ages. Wolves talk little pigs or small girls in red robes. In ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ the wolf becomes “a seducer, a stalker of young girls, a metaphorical consumer of virgin flesh.” (Warner, 1999, 37) In literature of the nineteenth century the name of ‘Dracula’ towers over the Gothic era. Published in 1897 Dracula thrilled the late Victorian imagination with his blood sucking attacks, and the ‘lunatic’ Renfield seeks ‘life’ contained within the spiders or flies he disgustingly devours. The consuming of a life gains ‘possession’ of it and in Dracula “the blood is the life.” In an age of exploration deep into ‘Darkest Africa’ the English reading public were being regaled with tales of ‘savagery’ with glee by the popular press. ‘The Star’ led on the front page on September 20,1888, with a tale of an expedition to the Congo that witnessed:

“Loathsome cannibals, and who only attached themselves to Major Barttelot on condition that they were to be allowed to do what they pleased. What they pleased meant the wholesale robbery and murder of inoffensive villagers, followed up by a bout of cannibalism. These precious allies of British and civilised explorers are in the habit of eating their captives, and it is a common thing, says Mr. Brooke, to see human hands and feet sticking out of their cooking pots.” (The Star, 20/09/1888)

To the Victorian reader their England was a bastion of civilisation and faith in God that should turn these savages away from their path. What was also important however, especially after Darwin, was that there was the potential of the beast within us all, and aspects of Hyde alluded to in an earlier chapter. Perhaps the encounter with ‘Darkest Africa’ was seen as the modern equivalent of a space trip into un-chartered territory and it allowed thinking on how to approach ‘new people’ with ‘the scientific desire to systematize, to classify to museumize.’ (Wilson, 2003, 488)

The impact of the so called ‘From Hell’ letter by ‘The Ripper’ on October 16, 1888, connected into all the fears of the cannibal and the ‘un-naturalness’ of the hidden danger stalking London. It read:

“From hell.

“From hell.

Mr Lusk,

Sor

I send you half the Kidne I took from one woman and prasarved it for you tother piece I fried and ate it was very nise. I may send you the bloody knif that took it out if you only wate a whil longersigned

Catch me when you can Mishter Lusk”

Opinion is very divided as to these letters and how genuine they are, however credibility would appear to be given to about three of the hundreds of letters received by the police at the time, the ‘From Hell’ letter being considered one of three most likely to be genuine. This fear of ‘the other’ in society links closely to the notion of colonialism and the feeling that somehow the English were superior to the barbarism the Empire was supposedly coming into contact with. This is why when reports came back of the Shackleton Expedition to the Antarctic, where cannibalism was alleged to have occurred as food stocks dwindled, it was denied in the Press as something that could not have been done by an Englishman, and must have been the Inuit. This is the root behind the clamour for a foreigner as the perpetrator of the ‘Ripper’ crimes. To the Victorian mind there was somehow something ‘not English’ about it.

Yet in fact there was something very English about the whole notion of cannibalism and the fear of atrocity. Connecting back now to the earlier work on Sweeny Todd there was a literature of fear in existence that worked on the popular imagination. In‘Martin Chuzzlewit’ (close of ch. 36), Dickens refers to the contemporary fear of country people migrating to the cities, that on arrival they would be baked into pies.

The world of children’s skipping rhymes of the nineteenth century worked on by Iona and Peter Opie has shown the barbarism within many of the songs, this example being one sung around Liverpool in the nineteenth century “Baby and I were baked in a pie, The gravy was wonderful hot. We had nothing to pay to the baker that day, And so we crept out of the pot.” (Opie, 1951, 33)

Popular culture then utilised the barbarity in a way that the children sang about Charlie Peace in Chapter Three. Writers as well began to use repellent imagery of cannibalism to gain the fascination of nineteenth readers with the larger world that the explorers were encountering. Defoe’s ‘Robinson Crusoe’ has a scene in which a meeting with cannibals is described in some detail: ‘This was a dreadful sight to me, especially when going down to the shore, I could see the marks of horror which the dismal work they had been about had left behind it, viz. the blood, the bones, and part of the flesh of human bodies, eaten and devoured by those wretches, with merriment and sport’ (Defoe, 1869, 88)

To the Victorian middle-class mind, England was represented by the cricket grounds and the notion of fair play, ‘the other’ was somewhere ‘out there’ in the depths of Africa and the fringes of Empire; the bogeyman came when ‘the other’ trespassed into their own world, which is why the ‘Ripper’ struck such fear far beyond the confines of London.

Who, then, was the Victorian bogeyman? Basically the bogeyman is about fear and about how we react toward it. The fascination of the ‘Ripper’ is both repulsion at the crime and fear of the fact that the killer went undiscovered. ‘Fear’ has its origins in tales of childhood and our sanitised modern world often forgets the roots behind these stories and that lay behind the presence of the bogeyman. The ‘early’ beginning of ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ lay in a tale by Charles Perrault; here the wolf ‘hides under the covers, and urges the girl to “climb into bed with me.” The girl comments on “what big” arms, legs, ears, eyes, and teeth the wolf has, which ends with the wolf saying “The better to eat you with!” The wolf then “threw himself upon Little Red Riding Hood and ate her up.” In Perrault’s fairy tale, published in 1697, no woodsman comes to rescue her; and Little Red Riding Hood does not save herself.’ (Lombardi, site access, Sept 2006)

The role of this tale appears to be one of morality in which the wolf may lie within man and danger is out there, girls need to be both wary and protected. To the post Darwin world there also lay within man a beast, a Hyde who could come to the fore with the viciousness of the killer of ‘Sweet Fanny Adams,’ a destroyer of childhood. Victorian England attempted to explain away the bogeyman with the Protestant distrust of the hold of the physical image portrayed in picture form, the protestant ethic preached sobriety, thrift and hard work to the working classes; one in which the bogeyman would be kept away by the new science and understanding of the ‘modern age.’ Where suspicion rose it went hand in hand with prejudice and suspicion of the Jew or the immigrant, or of a world outside civilisation; the strange land of ‘the other.’ Marina Warner moved the whole debate on the figure of fear into our own world, one in which the internet, cable television and mass media have taken back into a ‘new age of confusion between image and reality…a realm of semblance, where appearance is all, and a flickering flux of mirages bewitches the senses into the expected responses, into trust faith, belief…we have re-entered the ancient, magical, image-worshipping terrain of Catholic imagination and practice.’ (Warner, 1998, 378) The more we explain, perhaps the more we want the mystery; the more we require the sighting of a ‘vampire’ in Birmingham. Perhaps no different to out Victorian forbearers we still look toward the unexplained and we wish to be afraid of the wolf that lurks outside our village walls.

Bibliography

Books

Davison, C.M citing Leslie Fieldler (2004) ‘Anti Semitism & British Gothic Literature, London, Palgrave MacMillan.

Opie, Iona & Peter, ed.(1951) Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Sweet, M (2001) ‘Inventing the Victorians,’ London, Faber & Faber.

Warner, M, (1999) ‘No, No, the Bogeyman, ’New York, Farrer Straus & Giroux.

Wilson, A.N. (2003) ‘The Victorians,’ London, Arrow Books.

Newspapers

Almond, P, ‘Take Cover: The new Goths are coming,’ The Sunday Times, June 11th 2006, p.1, citing Rear Admiral Chris Parry.

The Jewish Chronicle, Friday 5th October 1888, ‘Notes of the Week,’ source contained on ‘Casebook Jack the Ripper:’ http://casebook.org/press_reports/jewish_chronicle/jc881005.html

‘The Star’ 20th September 1888. Edition taken from: Jack the Ripper Casebook: http://casebook.org/press_reports/star/s880920.html

Fiction

D Defoe, ‘Robinson Crusoe,’ Oxford World Classics, 1998 edition, first published 1869.

Internet

Lombardi, E, ‘Little Red Riding Hood Uncloaked,’ http://classiclit.about.com/cs/productreviews/fr/aa_redridinghoo.htm