Impact of E-commerce on the Airline Industry

Introduction

E-commerce is defined as the purchase or exchange of goods and services over the Internet, between individual consumers, businesses or other organisations. It started out in the 1970’s as an industry standard called EDI (Electronic Data Interchange) which was a structured way of exchanging data between companies, mainly to simplify purchasing and supply procedures. However, EDI required the usage of expensive and complicated private networks which nullified its impact on consumers and small enterprises. The advent of the World Wide Web, which used the Internet and its low cost and ease of entry, radically changed this landscape to allow access by individual customers as well, thus revolutionising trade forever (Rincon et al, 2001). The convenience of being able to purchase goods and services without time and geographical constraints has led to the rapid uptake of e-commerce, and one of the sectors at the forefront of the e-commerce revolution has been the air-travel industry. Surveys show that these are among of the most popular of all transactions conducted online, and over the next few pages we shall examine why this is the case and take an in-depth look at the impact of e-commerce in the sector.

E-commerce sector briefing- Impact on the airline industry

A lot of the e-commerce principles and methodologies were actually pioneered by the airline industry. The first exchanges of business-to-business electronic information owe their existence to the airline industry. The availability of reliable low-cost communications through the Internet enabled airlines to calibrate consumer supply-and-demand cycles, produce multi-pronged product marketing strategies and practice dynamic pricing structures (Smith et al, 2001, Interfaces).

One of the earliest pioneers of e-commerce in the world was American Airlines, which developed the Sabre computer-reservation system to track seat availability across the hundreds of flights that it operated daily. It did this almost 45 years ago! This system and others like it have revolutionised air-travel behind the scenes, by “improving product distribution and customer service through dynamic ticket pricing and frequent flyer programmes” (Smith et al, 2001, Interfaces). These have since evolved into GDS (Global Distribution Systems), which have consolidated information from airlines across the globe and in the process brought airlines, agents and consumers together in one big online marketplace. These have expanded to include ancillary services such as hotel reservations and car rentals, thus providing customers with more convenience and value-for-money while at the same time helping airlines to improve efficiency and generate extra income.

During the 1950s, American Airlines was faced with the problem of handling passenger numbers that were too great for the simple manual techniques used at the time – something like 26,000 per day. After five years of collaboration with IBM, they launched the Sabre automated reservation system, which decreased the average time of booking a reservation from 45 minutes to three seconds. An evolution of the Sabre system is still in use today, and at the turn of the 21st Century was handling something like 12 million transactions per day. American Airlines continued to build on their lead in this field, and by the early 90s were the first major airline to introduce discounted fares for travellers who could be flexible with their requirements – all made possible by e-commerce technology. This had the added positive of filling up otherwise empty seats, to the extent that $1.2 billion of American Airline’s profits over three years were attributed to the savings made by the yield-management engine built into their e-commerce interface.

American Airlines were quick to capitalise on the potential of the Internet, which would be a vital step in gaining a march over their competitors. In the United States, an estimated 26 million households booked travel arrangements online, with revenue generated from online ticket sales standing at about $38 billion. It continues to grow at an exponential rate, with European transactions in 2003 doubling that of the previous year, with a 120% increase in revenue. But more tellingly, reservations for air travel increased six fold.

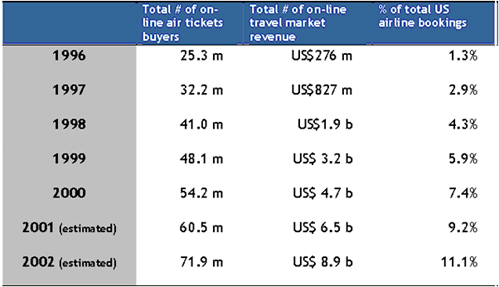

The table below shows the results of (a somewhat old) study into the number of online bookings in the US airline industry over a five-year period around the turn of the century. It’s a useful indicator of where things are headed, although the exponential growth of online air-travel bookings has probably outpaced these old studies, so the limitations must be kept in mind.

Figure 1: Online Bookings of Air Tickets (Shon et al, 2003)

It can clearly be seen that the trend towards online sales is increasing, and so is the amount of sales dollars (or Pounds) spent on these transactions.

More useful statistics about the importance of the air-travel sector can be found in the results of a Spanish study into the impact of e-commerce on the travel industry. According to de Alarcon (2005, Telefonica CSR), online travel companies are the number one driver of B2C growth in the European e-commerce arena. The table below shows that four of the top five e-commerce websites are travel based.

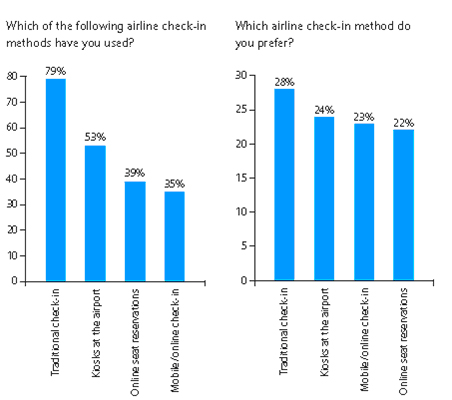

A survey by Barclaycard points that an increasing number of people prefer to use on-line check-in systems, including the latest mobile-phone based solutions, to check in and complete other formalities for their flights.

Figure 2: Check in Methods for Business Travellers (Barrow, 2006)

While 39% and 35% of business travellers currently use online and mobile check-ins respectively, that number is expected to rise to 85% in either case by 2015 (Barrow, 2006). This points at another trend that e-commerce is now fostering – that of one-stop travel shops, where all of a customer’s travel needs, whether they be check in services or hotel reservations are handled by one provider, with the flight serving as the focal point as opposed to the being the only component of a ‘one-box sale’.

Travelocity.com is one of the pioneers of this concept. By tailoring distribution methods to market needs, the solutions provided by lastminute.com are best suited to their customer’s itineraries and budgets. Customers can provide additional specifications, like chosen airlines, and these are then coupled with car rental packages or deals on hotel rooms. The customer thinks he is getting a good deal (which in fact he is, considering the cost he would pay to purchase all the services independently) but this also allows the supplier to make additional revenue from the added value of these bolt-on packages. This functionality would not have been possible without e-commerce platforms. Airlines themselves can use such packages to retain customer loyalty and differentiate themselves in a market where deregulation has provided a rather homogenous choice of flights.

So what is the impact of all these new opportunities and methodologies? For the air-travel industry itself, the most important effect is the redefinition of their relationship with the customer. Recent ticket booking mechanisms forge a much closer relationship between the business and its clientele by offering customers a much more personalised solution, for example, the interface provided by Travelocity which allows customers to specify all their preferences for their journey before providing them with results that match those specific requirements. As mentioned before, this provides significant opportunities to add on extra services and drive revenue.

The next thing is the change in the product/service profile. Before the advent of e-commerce, the customer would simply buy a ticket only when he needed it, as he didn’t have the information for making an ‘impulse’ purchase based on pricing and availability. That left airlines open to dips in demand. Now, with GDS, airlines can convert consumer surplus into producer surplus (Jarach, 2001, Journal of Air Transport Management). This is done through flexible pricing, where excess seating capacity can be utilised by offering last-minute deals through sites like lastminute.com

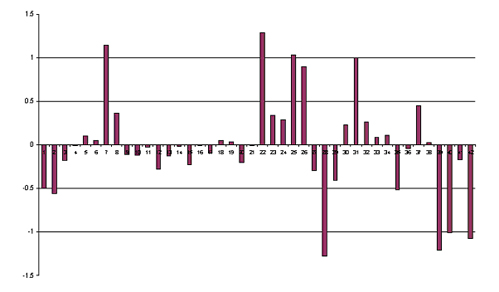

The impact on the supply-chain process also needs to be taken into consideration. With e-business platforms reducing supplier response times, there is more time to properly plan offers and thus increase their effectiveness. This also increases the efficiency of the B2B tender process, and since the travel companies can now shop around and compare prices with greater ease (much like their customers now can), the potential exists for savings on overheads to the tune of 5-20%, with 13% reduction in operating costs on average (Jarach, 2001, Journal of Air Transport Management). In fact, analysis of the impact of e-commerce on the productivity of different industry sectors shows that the air travel industry overall recorded an increase in productivity to the tune of 1%, as evidenced by its bar on the graph below [air travel is No. 31] (Rincon et al, 2001), better than the negative slide for the others which were struggling from the effects of the dot-com bust at the time of this study.

Figure 3: Productivity Impact of E-commerce on Airlines (Rincon et al, 2001)

Last but not least, the actual cost per transaction goes down considerably with e-commerce based transactions as opposed to traditional ones. Online promotions are not only much cheaper than traditional promotions, such as travel catalogues and media advertising, but their interactivity and possibility of personalisation also makes them more effective (de Alarcon, 2005, Telefonica CSR). A paper ticket costs on average five euros more than an e-ticket when everything is taken into consideration. And let us not forget that with GDS and CRM-based reservation tools, the middleman i.e. the travel agent, can be cut out, and thus the 5-25% commission that these charged can now be either passed on to the customer in savings or retained by the company as profit.

Which brings us neatly to the impact e-commerce in the air-travel industry has on the consumers. Obviously, there is a cost saving to be had in more ways than one, both with the possibility of direct ticket purchases as well as flexible seat-prices and promotions. The Internet has also made possible the conception of low-cost airlines, which by their very nature rely on CSR and GDS and the other benefits of e-commerce mentioned above to keep their operating costs to a bare minimum, thus resulting in low fares for the consumer.

The Internet has opened up the floodgates of choice and information to the customer, equipping him with the knowledge and awareness to make the right decision based on his/her needs. The customer is no longer restricted by traditional constraints such as geographical location and accessibility, and he is armed with a myriad of choices from which he can pick the best deal.

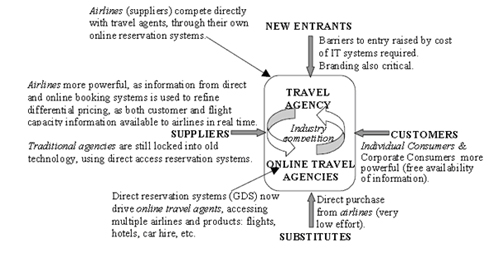

The graphic below sums up the impact of e-commerce on all the players in the air-travel industry. As always with every new business revolution, there are some who lose out (travel agents) but ultimately, the major players (the airlines and the consumers) stand to gain hugely from the e-commerce revolution (Heartland, 2001, also graphic below).

Figure 4: Impact Of E-commerce on Airline Industry (Heartland, 2001)

Conclusion and Recommendations

We have already established the pioneering role played by airlines in establishing the e-marketplace and their significance in today’s e-commerce arena. The initial forays made by air-travel companies prove that while the e-commerce platform’s hi-tech approach could bring major rewards, it also carries risks that need to be ascertained and controlled so that they don’t cancel out the positives that have been brought about.

To survive in the modern marketplace, air-travel businesses need to give consumers what they want, which is low prices and a wide choice. E-commerce affords them a way to do that, but to utilise it without diluting revenue, the airlines need to implement yield-management systems that can optimise revenue. These systems look at historical bookings and probable trends to forecast passenger’s willingness to pay the asked fares. According to Yang (2001), the revenue management system should instantly determine the flights, itineraries, prices and number of seats to put on the web, as well as constantly monitor the markets for relevant indicators. Only under these circumstances would the airline be able to dynamically, optimally and proactively price all seats at varying price structures in a real-time response to customer requests.

New technology necessarily requires a considerable amount of investment. While a case could be made for the advantages afforded by the investment being worth the cost, the fact remains that small and medium enterprises may not be able to afford such expenses. This gives the larger enterprises even more bargaining power and without proper regulation, they could effectively dictate the market. At the moment, the customer stands to benefit the most from the e-commerce revolution, which is why some players are not fully committing themselves to the technology yet. But the expense and complexity of the system means that there is a possibility of increasing industry concentration handing too much power to a small number of major corporations, which will then correspond into uniform pricing strategies, witness the price-fixing scandal involving BA and Virgin Atlantic (Chang et al, 2003, Journal of Air Transport Management).

This definitely makes a case for regulation via legislation. However, legislation has its own issues, namely those of jurisdiction. If a customer is based in one country and the business in another, which country’s rules would apply? No two countries would have a uniform set of rules when it comes to dispute resolution and the like, so this is a major problem. This must be addressed before reassurances can be passed on to consumers.

According to de Alarcon (2005, Telefonica CSR), one of the major reasons people don’t conduct transactions online is security fears. In 2004, 72.1% of Spanish Internet users had never purchased anything online. Their reasons were a distrust of the payment methods and fear of providing personal information over the Internet. These echo the sentiments of millions of people who have never taken the leap of faith and bought something online because they fear their personal/private data might be misused by online fraudsters, and the rise in the number of the latter certainly won’t do anything to allay their fears. Sometimes the factors might be societal as well. For example, people in the Far East have traditionally abhorred credit cards, which leaves them out of the e-commerce loop- and what about the people who can’t take advantage of these offers because they can’t afford a personal computer to access the Internet?

Taking some of the above factors into consideration, the following points of action could be implemented-

- Focus on customer relationship management to make the e-transaction process more personal. This will give customers what they need and form the basis for loyalty.

- Use CRS to market tickets on the basis of flexible prices and last minute availability.

- Market tickets through channels that incur the lowest transaction cost.

- Establish part ownership of GDS, so fees and commission for usage of the system by brokers return to the airline.

- Add value by bolting-on extra services such as car rentals and hotel bookings, and forge relationships on a referral-based scheme with preferred partners if lacking in their own infrastructure (Elias, 1999).

References

Shon, Z; Chen, F.Y. and Chang, Y (2003) Airline e-Commerce: The revolution in ticketing channels, Journal of Air Transport Management, Vol. 9 Issue 5 Pg 325-331

Jarach, D (2001) The digitalisation of market relationships in the airline business: the impact and prospects of e-business, Journal of Air Transport Management, Vol. 8 Issue 2 Pg 115-120

De Alarcon, R.F; Molina, M and Feliz M (2005) Electronic Commerce Applied to Tourism, Telefonica CSR

Barrow, S (2006) The Barclaycard Business Travel Survey 2005/2006, Barclaycard Business

Rincon, A; Robinson, C and Vecchi, M (2001) The Productivity Impact of E-Commerce in the UK, 2001: Evidence From Microdata, The National Institute of Economic and Social Research

Smith, C.B; Günter, D.P; Rao, B.V and Ratliff, R.M (2001) E-Commerce and Operations Research in Airline Planning, Marketing and Distribution, Interfaces, Vol. 31 Issue 2 Pg 37-55

Yang, S (2001) E-Commerce in the Airline Business, PROS Revenue Management

Heartland (2001) ‘E-Commerce’s Impact On The Air Travel Industry’, Heartland Information Research Inc., Report SBAHQ-00-M-0797, prepared for US Govt. Small Business Administration, Washington DC.

Chaves, I.G; Martins, H.S and Fernando, B.E.M (2003) A Secure E-commerce Platform to Enable the Worldwide Use of Standards , Portuguese Institute For Quality

VeriSign White Paper (2006) VeriSign Inc

Koc, K.C; Pongnukit, P and Thingthanatikul, W (2003) Analysis of E-Commerce Security, Oregon State University Press

Albrecht, C; Bombard L; He, B and Malone, S (2001) Building Trust for Electronic Commerce- An evaluation of SSL and SET, Cornell University Press

Thomas, S.A (2000). SSL and TLS essentials securing the Web, Wiley

Wagner, D and Schneier, B (1996) Analysis of the SSL 3.0 Protocol, The Second USENIX Workshop on Electronic Commerce Proceedings, USENIX Press

Briggs, J (3rd October 2006) Evaluating E-commerce Sites, Available online at URL: http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd – Accessed 03/12.2007

McPhee, L and Drucker, P (2000) Tips & Tactics for Conducting E-Commerce, Goldhirsh

Elias, E. (1999) Internet Commerce: Transforming The Travel Industry, SRI Consulting. Available online at URL: http://www.commerce.net/research/ebusiness-strategies/1999/99_34_r.pdf – Accessed 04/12/2007