Lifelong Learning Plan

Introduction

The term ‘lifelong learning’ is loose in nature and can encompass liberal, vocational and social aspects of learning, depending on who is using it (Field, & Leicester, 2003). It rejects the school/post-school division (ibid) and is defined as deliberate learning which can, and should, occur throughout each person’s life (Knapper, & Cropley, 2000) to the benefit of the individual and society as a whole.

The nature of teaching, is that teachers are at the interface of the transmission of knowledge, demands that teachers particularly engage in continual, career-long learning. Teachers need to maintain and improve their contributions to the profession, and also, if they wish to instil a disposition to lifelong learning to their students, demonstrate and model their own commitment to it (Day, 1999).

This paper will identify the lifelong learning needs of a group of higher education teachers at an institution in Saudi Arabia, and will then outline learning outcomes, teaching approaches and assessment procedures.

Needs Assessment

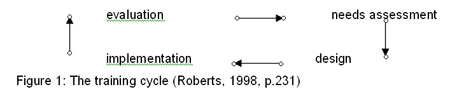

Assessing the needs of the trainees is an important and recurring part of any training cycle, as seen in the figure below:

In order to gain support from teachers for any training programme, their opinions need to be sought as there is a direct link between ownership of the training and commitment (Roberts 1998). The process of articulation is a major way of securing this commitment and involvement (Rubin 1978). Therefore a collaborative method of assessing the lifelong learning needs of the teachers was chosen where the participants were asked their opinions before embarking on the design of the course. The method used was ‘nominal group technique’ where participants are asked to suggest and then rank ideas. The process is as follows:

- Individual generation of ideas;

- Recording of all participants’ ideas (in a round-robin format);

- Group discussion of all generated ideas;

- Preliminary vote to select the most important ideas;

- Group discussion of the vote outcomes;

- Final voting on the priority of items.

(Jones, 2004, p.22)

The advantages of this strategy are that all participants have an equal voice, a lot of ideas are generated and a solution is reached at the conclusion of the session (ibid). In this case, after asking the participating teachers in which area they felt they needed further training to assist their lifelong learning, the conclusion reached was that the most important issue was further education in the use of technology and its applications to the classroom.

Learning Outcomes

The ongoing growth of information and communication technology (ICT) has created an enormous challenge for education, with its implementation at the forefront of many local, national and international policy reforms (Wong et al., 2008). Despite many institutions now being technology rich, there are reports that the actual implementation of the use of ICT in teaching is minimal (Cuban et al., 2001). It is suggested that the teacher is the key to this implementation beyond any other type of barrier (Wood et al., 2005); therefore it is essential for teachers to receive high quality training in how to use new ICT in their classrooms for the implementation to be successful.

As well as being a useful tool for the classroom, it is suggested that ICT will also provide more flexible and effective ways for the lifelong professional development of teachers, from video conferencing with other professionals, to websites with information about professional development and forums where experiences can be shared (Jung 2005). Therefore the learning outcomes of this course will focus not only on teachers learning how to use ICT in the classroom, but also on how to use ICT to develop professionally and connect with other teachers. Therefore the learning outcomes for the course will be as follows:

- develop an understanding of how the use of ICT can enhance the learning experience for students;

- integrate ICT into some aspects of the classroom;

- investigate how ICT can be used to develop professionally.

The actual content of the course will not be defined and instead a ‘bottom-up’ approach will be used where the teachers are enabled to pursue their own interests in the use of ICT and are encouraged to explore ideas, rather than being taught through traditional workshop input sessions (Haydn & Barton, 2007), as is discussed in the next section.

Teaching Approaches

Lieberman (1996) identifies four settings for teacher training: i) direct teaching, for example in the form of workshops or conferences, ii) learning in school, for example peer coaching action research, iii) learning out of school, for example through partnerships or at professional development centres, and finally iv) in the classroom, through student feedback and response. Traditionally, technology training for teachers has focused on direct teaching methods, mainly workshops and courses, which have been shown to be ill-suited in assisting teachers to apply the use of technology to the classroom (Brand, 1997). Other researchers have suggested alternative means of training teachers to use technology, utilising settings other than direct training. Koehler et al. (2007) use methods which put the teacher in an active rather that passive role, and ask teachers to design technology to find solutions to educational problems. They argue that teachers can then discover how to learn and think independently about technological uses in the classroom. Similarly, a graduate programme has been devised where there is no focus on specific technological tools, but the students discover how to apply those which are most relevant to their own situation through community learning, and a further programme instigated student-teacher mentor partnerships where the teacher and the student worked together, with the teacher providing the content and the student providing the technological knowledge (Reil et al., 2005).

Based on evidence from the literature, a non-direct method of training was chosen, using a combination of individual action research, mentoring and classroom research, where participants meet regularly to report and share their progress, as shown in the sample resources below.

Sample Resources

For all the sample resources it is assumed that the participants have access to a computer with the internet. A sample will be shown for each learning objective and can be found in the appendix.

Sample 1 is a form of action research, that is, the “collection and analysis of data relating to the improvement of some aspect of professional practice” (Wallace, 1998, p.1). It is an introduction to some of the technological tools available to teachers and the participants are encouraged to analyse their usefulness to their individual situation and then share and discuss their findings. A further activity may include participants observing other teachers using some technological tools and critically reporting the usefulness to the group.

Sample 2 is classroom research directed towards beginning to integrate technology into the classroom. It uses a specific application of technology, that of setting objectives for students, and asks participants to critically evaluate the success of the experiment. Further activities would include the participants finding a ‘knowledgeable other’ to mentor them in implementing a form of ICT in the classroom, and working with students to discover those aspects of ICT most useful to them (Prensky 2007).

Sample 3 is an investigation into how ICT can be useful for professional development. It asks participants to research and report on their experience using an online teachers’ forum. A further activity for this learning objective might be searching for and sharing websites with useful online resources for the use of technology.

Assessment

As was shown previously in the training cycle, assessment is an important part of training – both the assessment of the participants’ progress and assessment of the course itself. Without assessing the achievements of the participants, it is difficult to see how rational educational decisions about the course can be made (Hughes, 2003), which are needed in order to assess their further needs within the training cycle.

Ross and Bruce (2007) propose that self-assessment is a powerful tool for teachers to improve achievement. They argue that teachers, as self-regulating professionals, instinctively self-observe and make judgements about how well their goals have been achieved through analysis of student performance as evidenced by student utterances, their work and test results. While it has been suggested that there are limitations to self-assessment, for example that the participant’s view of their ability may not coincide with the actual ability, it has also been reported that participants are often more critical of their own ability than other evaluators may be (Darling-Hammond 2006), suggesting that people under- rather than over-estimate their abilities in self-assessment. However, Ross and Bruce (2007) suggest that it is essential to include other assessment tools as a checking mechanism, for example peer-assessment, to avoid any self-inflated reports of achievement.

This form of assessment suggested for this course, therefore, is a mixture of self- and peer-assessment. Participants would complete a questionnaire before and after the course to assess their knowledge and use of ICT, for example:

For the ICT applications below, rate your current knowledge.

1 = I do not know what this is.

2 = I know what this is but do not use it.

3 = I use this personally, but do not know how to apply its use to the classroom.

4 = I apply this to the classroom.

Blackboard Podcasts

Second Life Blogs etc.

While this is a very simple questionnaire which cannot gage the full extent of the participants’ knowledge of ICT, it could be used as a starting point for a discussion of the participants’ knowledge at the start of the course and an evaluation of what they have achieved at the end, when presumably each participant would have more answers of ‘4’ than at the beginning of the course. If they did not, there should be an investigation of why improvement had not been made and whether that was a general problem for all the participants, and therefore the course, or if it was an individual case.

In addition to the self-assessment it would be useful for the participants to observe each other periodically throughout the course to offer value judgements, to respond honestly and to promote the work of the other as a ‘critical friend’ (Costa, & Kallick, 1993). These evaluations would also be used as an assessment of the participants’ progress during the course.

Conclusion

There is an emerging consensus that the initial training teachers receive is no longer sufficient and should be sustained with further and continuing development throughout the teacher’s career (International Labour Office, 2000). This is especially the case with the use of technology as training is critical to ensure teachers keep up to date with the rapidly changing medium and classroom environment (Lawless & Pellegrino, 2007). In addition, research has shown that teachers who view themselves as proficient users of technology are more likely to integrate technology into the classroom (Ivers & Pierson, 2003). In an attempt to address this issue, this paper has outlined a lifelong learning plan for a group of higher education teachers with respect to further education and training in the use and implementation of technology in the classroom and for professional development. In training the teachers it is hoped that bringing technology into the classroom would mean the students would benefit from a learning environment which can stimulate higher order thinking skills, cooperative learning and the multi-modality of learning (ibid), which in turn, can only benefit society in the future.

References

Brand, G. (1997). What research says: training teachers for using technology. Journal of Staff Development, 19(1), 10–13.

Costa, A.L. & Kallick, B. (1993). Through the lens of a critical friend. Educational Leadership, 51(2), 49-51.

Cuban, L., Kirkpatrick, H. & Peck, C. (2001) High access and low use of technologies in high school classrooms: explaining an apparent paradox, American Educational Research Journal, 38, 813–834.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Powerful teacher education: Lessons from exemplary programmes. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Day, C. (1999). Developing teachers: The challenges of lifelong learning. London: Routledge.

Field, J. & Leicester, M. (2003). Lifelong learning: Education across a lifespan. London: Routledge.

Haydn, T. & Barton, R. (2007). ‘First do no harm’: developing teachers’ ability to use ICT in subject teaching: some lessons from the UK British Journal of Educational Technology Vol. 38(2),365–368.

Hughes, A. (2003). Testing for language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

International Labour Office (2000). Lifelong learning in the 21st century. Geneva: International Labour Office.

Ivers, C.S. & Pierson, M. (2003). A teacher’s guide to using technology in the classroom. Washington DC: Libraries Unlimited.

Jones, S. C. (2004). Using the nominal group technique to select the most appropriate topics for postgraduate research students’ seminars. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice. Vol. 1(1),20-34.

Jung, I. (2005). ICT-Pedagogy Integration in Teacher Training: Application Cases Worldwide. Educational Technology & Society, 8 (2), 94-101.

Knapper, C. & Cropley, A.J. (2000). Lifelong learning in higher education. London: Routledge.

Koehler, M.J., Mishra, P. & Yahya, K. (2007). Tracing the development of teacher knowledge in a design seminar: Intergrating content, pedagogy and technology. Computers and Education, Vol. 49, 740-762.

Lawless, C.A. & Pellegrino, J.W. (2007). Professional Development in Integrating Technology into Teaching and Learning: Knowns, Unknowns, and Ways to Pursue Better Questions and Answers. Review of Educational Research, 77(4), 575-614.

Leiberman, A. (1996). Creating intentional learning communities. Educational Leadership. Vol. 54(3), 51-55.

Prensky, R. (2007). How to teach with technology: Keeping both teachers and students comfortable in an era of exponential change. Emerging Technologies for Learning 2(4).

Reil, M, DeWindt, M., Chase, S. & Askegreen, J. (2005) Multiple strategies for fostering teacher learning with technology. In C. Vrasidas, & G.V. Glass (eds.). Preparing teachers to teach with technology. Place:IPA, 81-98.

Roberts, J. (1998). Language teacher education. London: Arnold.

Ross, J.A. & Bruce, C.D. (2007). Teacher self-assessment: A mechanism for facilitating professional growth. Teacher and Teacher Education, 23, 146-159.

Rubin, L. (1978). The inservice education of teachers. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Wallace, M.J. (1998). Action research for language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wong, E. M. L., Li, S. S. C., Choi, T.-H., & Lee, T. N. (2008). Insights into Innovative Classroom Practices with ICT: Identifying the Impetus for Change. Educational Technology & Society, 11 (1), 248-265.

Wood, E., Mueller, J., Willoughby, T., Specht, J. & Deyoung, W. (2005). Teachers’ Perceptions: barriers and supports to using technology in the classroom. Education, Communication & Information, Vol. 5(2), 183-206.