National identity, in terms of socio-political structures

With detailed reference to Moolaadé (Ousmane Sembene, 2004) and Kandahar (Mohsen Makhmalbaf, 2002), discuss the notion of national identity, in terms of the following contexts: Socio-political structures; Aesthetic forms.

National identity is a common concern in modern narrative, and is increasingly integrated within individual national cinematic depictions. The focus upon this topic does not arise per chance, nor is it a straightforward homogeneous or unitary phenomenon. National identity has been challenged, reinterpreted and rediscovered time and time again over the course of history. However, in this increasingly modernising world that caters for over six billion people, the concern for adequate representation and depictions of various national identities comes with some force. The relationship between national identity and modern filmmaking has constructed a unique instance where the visual becomes entwined with its identity; the landscapes, communities and people themselves aesthetically reflect the position and challenges towards a coherent national identity. This inter-textual, or inter-filmic, representation of national identity in Iranian and African cinema, demonstrated through both the social and political structures and aesthetic forms of Makhmalbaf’s Kandahar (Makhmalbaf, 2002) and Sembene’s Moolaadé (Sembene, 2004) will be the focus of this essay in the exploration of such.

The recently internationally renowned cinema of Iran was established earlier in the late seventies, offering an alternative cinema ‘that is fascinating, even astonishing, for its artistic sophistication and passionate humanism’. After the 1979 Islamic Revolution Iranian cinema produced films of natural cinematic quality, exploring conflicting indigenous values found across their culture, society and politics. The films themselves reacted with a genuine social consciousness towards real life people and problems: ‘the world of cinema was our window to a modernity we experienced only vicariously’. However all filmmakers were inundated with censorship rules that controlled the film industry and the very sustenance and meaning of the films they were making. These rules took away some artistic creativity with themes filmmakers wanted to explore, resorting towards a creation of symbolic communication in exploring these social and political concerns. However some filmmakers took on board positives from such constraints, finding more auteuristic and innovative ways to explore the contemporary milieu. Consequently the strict guidelines behind the direction and production allowed this multi-layered censorship system to determine many filmmaking structures, subject matters and other creative processes such as female voyeurism in Iranian filmmaking.

Conversely the relationship that developed between the arts, society and the state was fuelled by this imposition. This relationship originated around the depiction of national identity, nearly thirty years since the Islamic Revolution in 1979 – ‘Iran is still involved in a great debate over its identity and direction as a society’ that is highly representative of its films. The cogent narrative coupled with symbolic interpretations of various boundaries, gender constraints, and everyday hardships are dominant aesthetic limitations that form an articulate instance and portrayal emblematic of contemporary people in Iran.

Some critics view a re-birth of Italian Neorealist film qualities within Iranian cinema, portraying filmic narratives of everyday people in everyday life; Iranian filmmakers bring forward the Neorealist qualities, emphasising ‘a poetic conception…. [Consequently] these directors do not represent a break with Italian Neorealism; rather they bring forward poetic qualities which were inherent in Neorealism from the beginning’ and improvise forthwith. However in Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s Kandahar, there is something more sinister at work, a realism that elopes from human qualities, portraying a potent resistance against the dominant social and political institutions that control their life; control their geographical movement; control their aspirations and ultimately control their death. The challenges this film poses to the wider world in its formulation and controlling of its inhabitants highlight the importance behind the image of national identity. It is created with an aesthetic that metaphorically supports the narrative discourse, characteristics of the people and dominant ideologies representative of their way of life. Reflecting this Iranian filmmakers generally use methods of poetic realism through their aesthetic direction, blurring the general image of Iran to the wider world as while ‘the popular image of Iran seems tied to the often extreme and hostile statements of its leaders, Iranian filmmakers present a very different view of their country.’

In Kandahar we experience from a female perspective the controls, boundaries and manipulation of life. A narrative that only progresses in minor terms shapes the film towards a culmination of events and issues that constitute a suppressed and dehumanised national identity; this is a film about accessibility, the complex cultural struggle and difficulties surrounding it. The film captures shades of Neorealism in a short yet intimate storyline of family relationships in a modern, “globalist” world. Creating a national identity for the individual is of common concern in more independent and emerging cinema such as Iran. This may be most indebted to presenting such in relation of an increasingly institutionalised global world where the underlying meaning of life and our purpose of identity is captured, contended, and deconstructed.

Makhmalbaf’s work has been described as ‘aggressive and psychodramatic’ confronting the more restrained and patient elements of previous Iranian cinema. Amidst this narrative that manifests psychological forces and problems (for instance, the protagonists unknowing of precisely where her sister is and whether she is still alive or not), intermittently play upon the protagonist’s mind all the while between confrontations with her place in society and discovering herself again in her country of origin she left many years before. This “other” perspective tends with ambiguous notions of the protagonist and director, establishing a physical distance and a psychological space from reality and unknowing with her culture, country, and ultimately her identity. Dealing with the journey and the impending proximity of her sister, also getting closer towards the physical boundary of countries, she combats within herself a sense of belonging yet utter dismal hope for such a place. Visually the audience is confronted with many social and political issues that largely affect the everyday life of everyday people.

The first major example is the aerial view of the harsh landscapes and mountains of Iran that look so bland and unforgiving. Also the fact that she can only enter the country via helicopter immediately suggests the issue of borders and the difficulties of crossing them. The difficulty behind migration in and out of the country is exemplified, demonstrating the strict political laws that govern the country and its culture. This opening introduces the notions of cultural boundaries and places the film in context with cultural identity. This “transcendental style”, an increasingly common convention in Iranian films, establishes the detailed representation of the bland and dull commonplace of everyday living. The disparity and disunity between society and their environment creates an almost stasis quality, a frozen view of life that begins and continues the manifestation of a monotonous lifestyle in a culturally and geographically desolate sight.

Supporting this Makhmalbafexplains that some ‘people do sometime travel around Iran, but those who leave the country and see beyond the borders do not return… Travelling is unheard of in Iran, even domestically. Iran… has in recent years even begun to regress. We are still orientated to our ancient past’. This highlights the issue of accessibility which is examined in many forms; the Red Cross station supplying wooden legs/mobility for those who have lost theirs in war; the difficulty of travelling from town to town with a reliable, trusted guide; limited accessible food and water sources, also not forgetting the initial aerial journey into the country. It is this access to Iran’s economy, society, and politics that are reprimanded throughout the film, distilling not just their national identity, but a true national identity. Through this the film also allows its audience to explore questions around women’s existence, evoking ideas of liberation and status. This, placed in the context of a society fractured by war against the background of globalisation and imperialism with evident efforts in the progression of political Islam, conducts Nafas and her journey subjectively, appropriating evidence of the confusion, hardship and barrenness behind ones identity.

Another important cultural factor that inhibits the protagonist, not only physically, but also as a figure of humanity that loses respect, intelligence, and understanding, is her veil (or burka). It not only physically impairs her sight (so eloquently illustrated at the climax of the film as she lowers the burka onto her face), but closes her off from the world around her in so many ways. It is another example of the boundaries of identity perpetuated from political, social, and cultural discourse, shaping the women of Iran with no real figure, stance or opinion. As this affects all women in the film, a sense of empathy is created towards the unapparent recognition of women’s national diaspora in Iran. They are calling for change in the modern world; a world where the ability to even walk freely across their homeland is plagued by the preying locations of land mines. At this time we only see help from foreign aid, which evokes quite a powerful image of accessibility, the need and struggle for it, as it floats helplessly from the skies (wooden legs dropped by parachute). Makhmalbaf exclaims that the ‘government should take the initiative in addressing this, but it has blocked progress for women.’ He continues, ‘as the world moved on from the classical era, we did not progress. We are still in a state preceding humanism, much less modernism and realism.’ This point illustrates the cyclical, some may say condemned existence of Iranian people, suppressed from modern growth through religion and politics. This also implies the innocent and fragile nature of a third world country that seemingly doesn’t know any better.

Due to censorship rules that still today do not allow any woman to touch anyone else, except her husband, children have been used to explore particular themes. In other words the use of children allows directors to explore metaphorically and symbolically the issues intended for adults. This however tends to further merge documentary and fictional understanding, generating a repressive attitude towards highlighting these factors, which can become very problematic. Moreover, ‘in their social and geographical inclusiveness, [children] represented a bid to redefine the co-ordinates of national and cultural identity… [and] guaranteed the reality of the values they embodied’. The confinement of artistic abilities in Iranian film dictates the very nature and superior socio-cultural and political context they are presented from.

In an interview with Hamid Dabashi, Mohsen Makhmalbaf comments loosely around the cultural traits of the country that stem from political law. He talks of a nation of ‘self-aggrandisement… pretence and hypocrisy… sexist…. But in [Makhmalbaf’s] opinion Iran’s greatest problem is [their] belief in absolute truths.’ He explains, ‘we can’t achieve democracy because everyone sees himself as being the holder of the truth’. Feeling his films challenge these dominant ideologies he comments that this ‘fundamentalism distracts us from perceiving the reality, and leads us down the path to fascism.’ It is these oppositions towards dominant social and political constructions and ideology that perpetuate his films with a convincing directive of Iranian representation and social culmination for change.

Interrelating these problems with Nafas’s journey and attainment with a rediscovery of national identity, she discovers the hardships by which these people are defined. Aesthetically an apparition of eastern realism, yet true to actuality, Kandahar establishes the simple motive in the minor ability to live coupled against the harsh canopy of the landscape and politics that amalgamates the Iranian national identity.

Linking the cross-cultural debate of national identity as a topic of concern, Ousmane Sembène’s Moolaadé will be examined with close comparison to one reoccurring image in the film that, I believe, holds many ideas behind national identity. It exemplifies a national identity that is constructed and maintained throughout all forms of social and political structures, including both men and women with how it needs to change.

Ousmane Sembène was a highly admirable man, passing away in 2007. He was a novelist, a filmmaker and held a significant role in political debate that rose with the postwar movement towards African decolonisation. His radical pro-independence attitude towards African people plays an integral part for much of his writing and film work. It was his work towards independence and affiliation to the role of women in their struggle for social and political freedom that capsulated his literature and films. The patriarchal structures that ran a country “unhindered” by female objectivism and opinion was Sembène’s foremost purpose for literary and filmic depictions that endeavored to revolutionise “the way things were”. His examination of postcolonial situations, treatment of isolation and general position of women in society can be seen in films such as Niaye (Sembène, 1964), La Noire de (Black Girl, Sembène, 1966), and Mandabi (The Money Order, Sembène, 1968).

The focus in this essay however (another passionate film from the narrative point-of-view of women) falls to Moolaadé, a film that also demonstrates a huge crisis with women’s freedom and their national identity. This film is largely contextualised to a move into the modern world, the changes that need to take place and the comeuppance of a patriarchal society. There are some women that oppose the various changes advocated in the film, and these women stand true to their cultural heritage and ancient tradition behind their society. Conversely, the opposing women, and children, challenge more than just old tradition; it is about women receiving their due power to control the course of their own lives. These are women who need change to survive in a male dominated society where their views have not been heard until now.

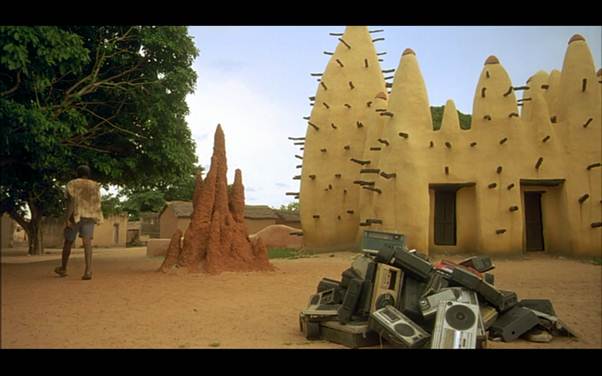

From the outset of the film the audience is appropriated towards the main issues of the film that, to name a few, concern women’s position is society, domestic place and more worryingly the evidence against female circumcision. This symbolic image portrayed early on in the film illustrates for the audience the imposing and obtrusive existence of modern accessories and clothing. This panning shot placed within the modern utensils displays not just the impact of globalisation, but more importantly the imposition it possesses with blocking the mosque; a more recent national trait of identity being distilled and literally “blocked” out of sight by modern conventions. Blocking can be seen throughout the film; especially social blocking and the organisation of groups of people are always depicted with the speaker, or speakers, in the front-centre; a stature issue and also a power trait for the individual(s).

Other counter-cultural images and instances from the film emphasise the notion of globalisation and modernity, a challenging of social and political structures, and of women’s struggle for equal say and cultural change. There are structures for both women and men. The males run the village. This is quite clearly demonstrated through the lack of speech when females are present, the giving of water on entry of men and the general mood and atmosphere illuminating the lack of connectivity between the two sexes. The latter example is shown very clearly in the one sex scene that lacked any form of togetherness, passion or mutual love. Among women, their levels of authority are evident in spiritual, biological and magical terms, all the while under male control. These structures are continually challenged throughout the film, reflected in the aesthetic construction. These assertions help formulate the creation of a new, coherent, applicable national identity in terms of integration into traits of the modern world.

From possessing Italian Neorealist and French New Wave aesthetic qualities, such as filming on location, indigenous costume and real life characters, help embody visual connotations that relate these films to European cinema. This helps the theoretical connectivity of the films aesthetics with its meaning and overall portrayal of national identity. The film concerns losing cultural traditions and practices that have been with the tribe for many, many years, and it is the loss of this cultural heritage that is of foremost concern to the male population (namely attitudes to female circumcision, among other things). Changing one thing may lead to many changes; something we find out through harsh realities in this film. Yet the women stand strong, don’t back down, and emphasise their need for change; not just for themselves, but for the lives of generations to come.

This introduces the issue of “protection” found in the film. One of the dominant female characters in the film, Collie, is asked by four prepubescent girls for “protection” from the initiatory rights of tradition: “being cut”, the films cryptic term for female circumcision. The spiritual prowess is needed from a strong female who previously had “protected” her daughter. This power is then challenged by the village’s female elders, the main performers of rituals such as the female purification. However the use of a colourful piece of string across the entrance to their living quarters is powerful and symbolic enough of tradition to protect the children; as breaking it would break ancient traditional practices. This major issue to the female population was regarded in the film by men as a “minor domestic issue”. This supports the ideological view point of a patriarchal run society whereby the ancient cultural tradition of purification is carried out regardless of opinion; let alone female opinion. This again shows the controlling and dismissive nature of the males, but also displays the importance of tradition, of social structures and the spiritual power of women. Conversely this current social structure is important for the women as it gives them hope for integration into an ideologically changing future.

Aesthetically the cultural traits and push for change are challenged in the very place they originate. From the focus and view point of a working village, we are placed in this culturally celebrated space. However, the village’s emergence into a modernising world is increasingly evident, and increasingly objectified as a negative imposition upon life. In the beginning of the film traditional instruments are lyrically played during the celebrations in the jungle and town while other daily activities are running smoothly. Further into the film problems surface. From the “womanising” Mercenary and evidence for escapism (listening to the “modern” radio) placed after these original instances, demonstrates these changes and their conflicting reception. Through the use of natural aesthetics the innate beauty of the country helps us to understand the importance of their surroundings with the relationship of their national identity. This juxtaposition is evident of an aesthetic struggle for the integration of modern technology and materialism within an indigenous, traditionally bound society.

Referring back to my original comment upon one reoccurring image within the film, the incorporation and explanation of the previous factors are magnified beyond recognition. This image displays a symbolic overhauling of previous cultural tradition with radios (significant of modernisation and materialism in a globalising world) foregrounding the burial ground (now ant-hill) of an ancient leader and the past (ancestry culture) juxtaposed with the mosque (modern religious following). Later in the film, as the radios pile up ready to be destroyed, burning now in a cloud of smoke they represent the extremely countered approach in obtaining a modern identity. This comes from the core concern of the influence such technology can bring; enlightening its listeners to the seemingly bigger and better things in life. It is not the music yet the modernised influence for change that concerns the males in the society. However it is too late, the radios have done their damage and given their awareness. Aesthetically symbolic of what their culture could become without addressing the modern world is demonstrated and amplified in the smouldering carcass of plastic and (symbolically) foreign inspiration.

Sembene’s films demonstrate the far more complex rendition of women’s struggle in a patriarchal society. However Ibrahima, the community’s heir and “handsome” young man returning from France, is a signification of hope for modernisation and a loss of old cultural tradition. This opens the door to attitudes that would allow the society to still function it a modern, “globalised” world, while retaining common values and modes of identity that will continue to relate them to their past. However in recent years African cinema has ‘turned their backs on politics and on a serious questioning of the oppression of women and the marginalised’ tending the idea that African cinema has ‘surrendered to European notions of what African cinema ought to be’. This loss of a cinematic identity in a more integrated world of national cinemas is just as reflective as maintaining the cultural traits and other dealings with national, personal and societal identity found in the films themselves. Rather than maintaining a cinema engrossed within innate social and political problems emblematic of their country and iconic narrative and filmmaking structures, African filmmakers may have instinctually adhered to more dominant cinematic forms for the countries film production survival. Is this too representative of the attitudes to integrating into a modern world? Does this lack of sustaining innate cinematic constructs and thematics relate to their static position in terms of modern progressions in society and culture, for both men and women?

Returning back to Makhmalbaf and his outlook upon changing the Iranian culture and identity towards the rest of the world, we can see a paralleling institution in African cinema. What these films national identities actually mean and portray in relation towards a global context, permit a nationalistic regard for one’s country, the issues within it and the aspiration for change in a modern world. The films demonstrate how the many forms of limitations and borders upon life manifest something against progression, and conjures counter-cultural representation that sometimes have to go to extremes, in physical, psychological, and geographical grief and anguish to ascertain their opinions. These two films interlink their passionate narrative with aesthetic recognition that will only ever support and display the crisis with national identity. Regarding the passage of women’s struggle for national suffrage in a culturally bound country illuminates these films within an important periodical examination of where the feminine ideal, with where and how womanhood fits in with their national identity among submissive social and political structures, is continually explored.

Bibliography

Akudinobi, Jude, ‘Durable Dreams: Dissent, Critique, and Creativity in Faat Kiné and Moolaadé’, Meridians: feminism, race, transnationalism 6:2 (2006), pp. 177 – 194.

Cardullo, Bert, In Search Of Cinema: Writings on International Film Art (Quebec: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2004).

Chaudhuri , Shohini, and Finn, Howard, ‘The Open Image: Poetic Realism and the New Iranian Cinema’, in Grant, Catherine and Kuhn, Annette (Eds.), Screening World Cinema (London and New York: Routledge, 2006), pp. 163-181.

Dabashi, Hamid, Close Up: Iranian Cinema – Past, Present and Future (London and New York: Verso, 2001).

Diawara, Manthia, African Cinema: Politics and Culture (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992).

Gadjigo, Samba, ‘Art for Man’s Sake: A Tribute to Ousmane Sembene’, Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media 49:1 (Spring, 2008), pp. 30 – 34.

Givanni, June (Ed.), Symbolic Narratives/African Cinema: Audiences, Theory and the Moving Image (London: British Film Institute, 2001).

Kumar, Deepa, ‘Afghanistan Unveiled, and: The Lost Truth (review)’, NWSA Journal 17:3 (Autumn, 2005), pp. 195 – 198.

Martin, Adrian, ‘The White Balloon and Iranian Cinema’, Pandora Archive (Written for Radio: Broadcasted September 1996), Available at –

http://pandora.nla.gov.au/pan/10772/20060909-0000/www.sensesofcinema.com/contents/01/15/panahi_balloon.html Accessed 19-04-2009.

Monaco, James, How to Read a Film, 3rd Edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000).

Orlando, Valerie, ‘Voices of African Filmmakers: Contemporary Issues in FrancophoneWest African Filmmaking’, Quarterly Review of Film and Video 24 (2007), pp. 445 – 461.

Russell, Sharon A., Guide To African Cinema (Westport, Connecticut and London: Greenwood Press, 1998).

Sadr, Hamid Reza, ‘Children in Contemporary Iranian Cinema: When we were Children’, in Tapper, Richard (Ed.), The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation and Identity (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2004), p. 227-237.

Sadr, Reza Hamid, Iranian Cinema: a political history (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2006).

Varzi, Roxanne, ‘Picturing Change: Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s “Kandahar”’, American Anthropologist 104:3 (September, 2002), pp. 931 – 934.

Weinberger, Stephen, ‘Neorealsim, Iranian Style’, Iranian Studies 40:1 (Febuary, 2007), pp. 5 -16.

Filmography

Niaye (Ousmane Sembène, 1964).

La Noire de…/ Black Girl (Ousmane Sembène, 1966).

Mandabi/ Le Mandat/ The Money Order (Ousmane Sembène, 1968).

Kandahar (Mohsen Makhmalbaf, 2002).

Moolaade (Ousmane Sembene, 2004).

Appendix 1

Appendix 2 1

2

3

4

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

Bert Cardullo, In Search Of Cinema: Writings on International Film Art (Quebec: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2004), p. 21.

Hamid Dabashi, Close Up: Iranian Cinema – Past, Present and Future (London and New York: Verso, 2001), p. 3.

Cardullo, In Search Of Cinema: Writings on International Film Art, p. 23.

Demonstrating the abilities of these filmmakers and concern for this issue: ‘Iranian filmmakers manage to address [their films] not with easy sloganeering or smooth sentimentality but with penetrating insight and a sure sense of storytelling basics as well as dramatic purpose. Iranian films’ most singular quality, however, may be a feeling of compassion for those who suffer’ – Ibid, p. 25.

Shohini Chaudhuri and Howard Finn, ‘The Open Image: Poetic Realism and the New Iranian Cinema’, in Catherine Grant and Annette Kuhn (eds.), Screening World Cinema (London and New York: Routledge, 2006), p. 164.

Stephen Weinberger, ‘Neorealsim, Iranian Style’, Iranian Studies 40:1 (Febuary, 2007), p.15.

Adrian Martin, ‘The White Balloon and Iranian Cinema’, Pandora Archive (Written for Radio: Broadcasted September 1996), Available at – http://pandora.nla.gov.au/pan/10772/20060909-0000/www.sensesofcinema.com/contents/01/15/panahi_balloon.html Accessed 19-04-2009.

See Appendix 1.

Chaudhuri and Finn, ‘The Open Image: Poetic Realism and the New Iranian Cinema’, in Grant and Kuhn (eds.), Screening World Cinema, pp. 163-166.

Dabashi, Close Up: Iranian Cinema – Past, Present and Future, pp. 205-206.

See Appendix 2 – demonstrated with a series of four continuity screen-shots, of linear narrative.

Dabashi, Close Up: Iranian Cinema – Past, Present and Future, p. 204.

Ibid, p. 205.

Of whom has to be her husband in real life also; no fictional marital relationships are permitted.

Hamid Reza Sadr, ‘Children in Contemporary Iranian Cinema: When we were Children’, in Richard Tapper (Ed.), The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation and Identity (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2004), p. 236.

Dabashi, Close Up: Iranian Cinema – Past, Present and Future, pp. 204-205.

Ibid, p. 205.

Ibid, p. 205.

See Appendix 3.

Russell, Sharon A., Guide To African Cinema (Westport, Connecticut and London: Greenwood Press, 1998), pp. 130-132.

See Appendix 3.

Jude Akudinobi, ‘Durable Dreams: Dissent, Critique, and Creativity in Faat Kiné and Moolaadé’, Meridians: feminism, race, transnationalism 6:2 (2006), p, 187.

See Appendix 4.

Ibid, p. 140.

Ibid, p. 141.

‘Some believe that we need to influence Iranian society, and think that, by publishing books and making films, we cause cultural change in Iran. But that’s not so. The work of cultural change would be to bring about a revolution wherein all people would arrive at decisions that may or may not be related to the aspirations of the revolution, but that would naturally result from the event. Instead, the atmosphere we live in only confuses people. Since the door to dialogue is closed and we are deprived of basic freedoms, people are left with little to consider.’ – Dabashi, Close Up: Iranian Cinema – Past, Present and Future, p. 206.

‘The centrality of motherhood, a key feminist tenet, in Faat Kiné and Moolaadé are unmistakable. Hence, Sembène uses Mammy’s disfigured back and Collé’s caesarean cicatrix to foreground injustice and oppression, to show that the inflictions of patriarchy are not superficial wounds, and, as battle scars from the war against subjugation, honor them. In this sense, a key issue here is the critical relationship these women, in vanguard roles, establish with certain orthodoxies, especially as both films offer unique frameworks for reevaluating certain logics of culture and paradigms of self assertion.’ – Akudinobi, ‘Durable Dreams: Dissent, Critique, and Creativity in Faat Kiné and Moolaadé’, p.192.