Research Report on Crag and Tulving’s Depth of Processing and the Retention of Words in Episodic Memory

Number of words: 2833

Abstract

The potential of human memory to interpret data has become a source of considerable worry for some period, and various hypotheses are being investigated in an attempt to comprehend the issue. Numerous theories have placed a strong emphasis on the organizational alignment of a human memory process. Theoretical models, on the other hand, emphasize the mechanisms associated with acquiring and recalling to comprehend the dissemination of knowledge. Instead of focusing just on the fundamental components of the human main memory, mechanisms like concentration, storing, preparation, and recovery were employed in the latest research to create a more sophisticated explanation of the structure. And 10 distinct tests were carried out to fulfill the report’s aim. This research included Twenty college individuals of both genders who were evaluated separately.

The individuals were subjected to a variety of stimuli in an attempt to better comprehend the mechanism of material comprehension and understanding. A participant was given a word on a tachistoscope for around 200 milliseconds before being posed a query to stimulate the participant to analyze the word to one of the many stages of evaluation. In addition, the individual was required to analyze the term at either a superficial or a somewhat deep degree. The individual getting examined will stare into the tachistoscope with one arm on a “Yes” answer key the other on a “No” reply key after the topic has been given out. In response to the inquiry presented initially, the respondent was anticipated to answer with a “Yes” or “No.” In summary, the findings showed that concerns about the definition of words elicited more cognition and hence better memory retention than queries on external characteristics or sound.

Depth of Processing and the Retention of Words in Episodic Memory

Introduction

The efficiency of the human memory mechanism has been extensively studied with the bulk of the findings focused on the fundamental elements of the working memory in connection to cognitive processing. Alternative views have focused their research on the many mechanisms engaged in language and memorizing. In this situation, the word process refers to the consecutive steps or aspects associated with the procedure of achievement and instruction of material, i.e., the data transfer from introduction to the material to recalling the identical data. Such research has presented numerous approaches that solely handle the distinct phases of knowledge transfer. Various steps are engaged in the activity of learning and remembering material. Numerous interrelationships exist in these phases to achieve data-flow efficiency. Nevertheless, there is a lag between when people are exposed to new information and when they recall it.

As a result, the present research focuses on the many mechanisms involved in remembering new information. Focus, processing, practice, and retrieving are a few examples of these procedures. Craik and Lockart have proposed a fresh perspective on human memory capacity (1972). The research was conducted in an unintended learning context, in which participants complete several focusing activities that require numerous mental processes and have an influence on learning. According to the findings, when individuals do various orienting activities that need additional effort in thinking and processing of the words presented to individuals in a question, they have a greater recall rate. This result can also be linked to the memory efficiency in controlled circumstances with no interruptions or refocusing tasks.

When contrasted to tests that do not have significant semantic components, including structural tests, a semantic centering test resulted in improved word retention. Furthermore, as contrasted to discordant inquiries, concerns of either approving or disagreeing were proven to produce higher human working memory. Whenever individuals are challenged to generate pictures (imagination questions) of words they see on the tachistoscope, they show remarkable word recall. The findings of the study have several ramifications. First, there’s a demonstration of how accidental and deliberate learning are related. As a result, retention is determined by the various processes performed on the material without any purpose of learning. The result also shows that there is a definite link between paying attention to the content of a word and remembering it. Whereas the recovery circumstances are kept the same, the differences in retention reveal the effects of programming procedures.

Method

Participants

The respondents in this research were a group of 15 individuals, including males and females. The University of Memphis had 5 males and Ten women in attendance, varying in ages between Nineteen to 45. All of the individuals were at minimum 18 years old, however, the overall age was 25 (M=24.73, SD= 6.92). Participants were 33 percent White and 66 percent, Black, in ethnicity. Individuals were recruited from dorms, lecture rooms, and the university library for the studies.

Materials

SuperLab 5 was the program utilized to enable the students to engage in the event. During the exercise, the respondent has instructed three sorts of tasks, including whether “a word was the upper or lower case if it rhymed with another word, and word category” (which might be as basic as inquiring if a word was only an animal or a piece of wood). There were no monetary rewards for taking part in the study.

Procedure

Every participant received a brief description of the research and a basic outline as to how the discussion would proceed at the start of every encounter. All queries or doubts raised by the participant were addressed. Following that, they were handed a written expressed agreement to review and approve. The participants were informed that they were contributing and even though they had the choice to say no or refuse to participate in the program at any moment. The information gathering for the activity could not commence until the participant had reviewed and approved the ethical approval (Seamon & Murray, 1976).

In a particular instance, the participant had any queries or worries, the investigator was close. The program posed three sorts of queries; if a word was upper or lower case, as to if it rhymed with a similar word, and what word group it belonged to. Did we enable the learners to rate? sample sessions while proceeding to the actual phase to ensure that they grasped whatever they have been undertaking. The overall duration it took every individual to finish the research activity was about five minutes. Whenever the person had completed the lesson, they were congratulated for their time and allowed to go.

Design

Multiple individual factors were included in this investigation. The depth analysis was the initial output factor. There comprised three degrees of cognition: Specific instance, which corresponded to the minimum degree of processing, Rhyme, which was middle, and Categories, which were uppermost. A Category phase consisted of questioning the respondent if the word was “upper or lower case”, a Rhyme phase consisted of questioning out whether words rhymed, and a Categories stage consisted of adding the word into a category. The next independent parameter was reaction kind, which was defined as whether the individual replied yes or no to the queries. Accurate identification became the major coefficient of determination, while reaction delay was the next. All quantitative procedures were performed employing SPSS Version 15 and an among variables ANOVA with a scientific relevance of p0.05.

Results

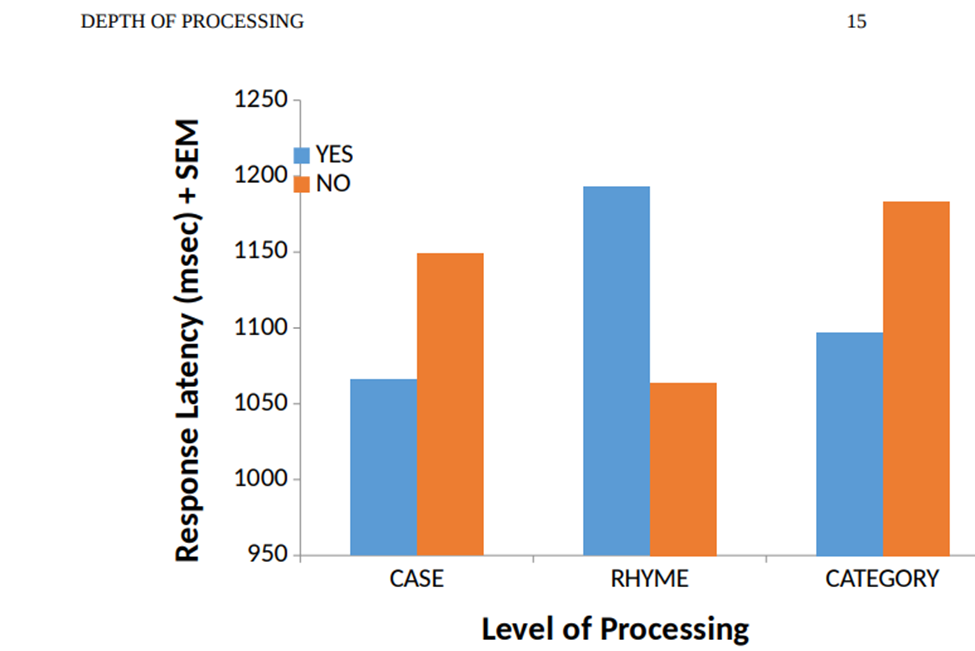

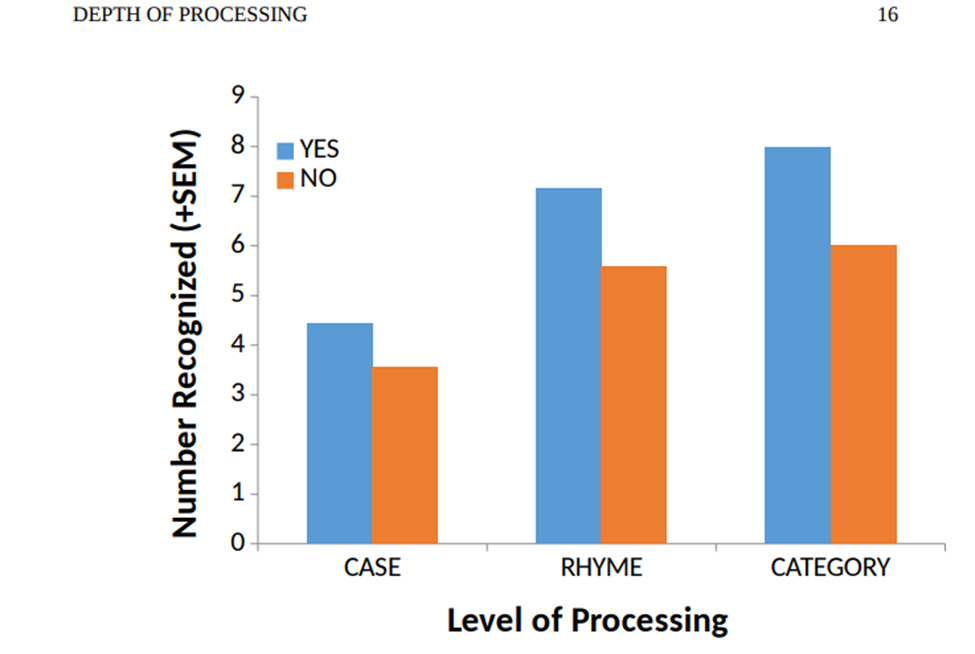

We looked at the results of the focal query “Either or not cognitive processes affect word retention” in each scenario to see if there were any great disparities among the depth of processing and word utilization. With precision F (2,26) = 3.123, p=.96, the Calculated value was numerically relevant. We examined the disparities of delay on the bivariate analysis, and F (2,.813) wasn’t significant. A two-way assessment of variance was used to generate both of these metrics. The degrees of analysis were linked to “Case, Rhyme, and Category”. The mean for Case was (M=4.45, SEM=.647), Rhyme was (M=7.15, SEM=.629), and Category was (M=8.00, SEM=.632).e

Table 1: Case, Rhyme, and Category to Response Latency

Table 2: Case, Rhyme, and Category to number recognized

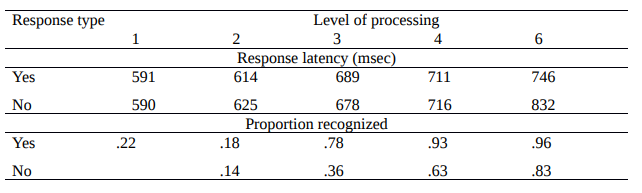

When it came to sentencing choices, recognition skills improved from 15% to 81 percent. The percentage of those who recognized no words climbed from 19% to 49%. The subject type impact was F (2, 46) = 118,.001, the answer pattern influence was F (1, 24) = 47.9,.001, and the Issue Type X Solution Style interaction was F (2, 46) = 22.5,.001), according to the regression analysis.

Table 3: Results for Experiment

Deeper depths were linked with prolonged response latencies, F (2, 38) = 27.7,.01, and subsequent displays were reacted to quicker, F (1, 19) = 18.9,.01, according to a NOVA. The evaluation of variance revealed profound impacts of best levels (F (2, 38) = 43.4,.01), recurrence (F (1, 19) = 69.7,.01), and reaction pattern (F (21, 19) = 13.9,.01) on recall findings.

Discussion

The findings did not substantiate the notion that word retention is influenced by cognitive depth. The Calculated result in one of the random parameters, latency, was not scientifically relevant, indicating that the duration it needed individuals to enter their replies was not substantial. Nevertheless, the next autonomous parameter correctness, appeared to have substantial impacts, suggesting that the various degrees of cognition may contribute to comparable correctness across all replies. The findings of the investigations demonstrate that when participants are exposed to diverse stimuli, the kind of assessment has a substantial impact on later working memory. When compared to superficial level word analysis, deep level word analysis produced better memory results. Encouraging answers in the early stages of encoding were linked to better memory performance than negative judgments or replies. Under both deliberate and accidental studying situations, these effects were seen on elements of recognition and recall. The next research was conducted to look into the causes behind better word memory when positive answers were offered. The findings showed that embedding complexity, instead of encoding depth, offered a better representation of the result. The finding showed that isolation effects also couldn’t explain the findings on their own.

Literature Review

Apart from what Craik and Tulving (1972) discovered with “depth of processing and word retention”, the findings revealed no link between delay and reliability but found a connection between precision and delay. With Baluch and Besner, it was discovered that we can possess a previously built cerebral pattern, and that translucent words were nearly usually handled in this manner and not owing to everything else. This relates to cognitive processes since it suggests that our unstable pattern may have a greater impact on our memory than the depth to which we choose to analyze specific words. This is relevant to our findings since we discovered that regardless of the level of processing, there may be an implicit previously established rhythm that aids in the retention of words. Similarly, to Craik and Tulving’s study, both superficial and deep cognition was evident throughout vocal processing (1972).

MRIs (Magnetic Resonance Images) were used to track the brain’s activation to discover if there was a combination of functionality and activation in the brain (Walla et al., 2001). The amount of false-positive throughout recognition assessments was shown to be dependent on the level of analysis throughout earlier encoding. The more deeply the prior research terms were encoded, the fewer false positives emerged. Furthermore, through the test stages, a definitive relationship was discovered among the brain activity generated by false positives and how deeply the research words were stored (Bentin & Katz, 1984). These false reports from the following trial stage evoked lower brain function if the research words were to be cognitively stored than when the research words were to be intellectually stored.

Implications

According to the findings it can be inferred that depth of cognition had an influence on word retention in this research. The primary impacts of delay, or the time it took the individuals to enter their replies, were not substantial. It did not affect the individuals’ ability to remember the words, regardless of the amount of cognition the queries required. Nevertheless, there were substantial principal determinants with correctness, indicating that employing varying rates of depth analysis resulted in continuous correctness in the replies of the respondents. The final findings refuted the concept of cognitive processes concerning word retention.

Limitations

Several individuals forgot which icons on the laptop corresponded to the desired response, whether it was z for no or / for yes, throughout the research. Succeeding session, have a sheet of paper available that specifies each key corresponds to which solution so that the players are not confused. Because the respondents were all in various locations during the event, it’s possible that their responses and attention were influenced. This might have been avoided if only one place had been chosen. Also, because the data set of 15 is limited, the findings may have been different if there were enough individuals, regardless of whether the figures were meaningful or not. The program included numerous issues, and I saw that around midway over, the attendees became impatient and began to speed through the remaining sections. The session might have been made faster or with more interesting questions.

Future Research

The findings raise the dilemma of perhaps we ought to consider if we have a cognitive pattern that helps us to recall or forget words. Further study might show that when it pertains to acquiring additional words and also having been able to remember them, depth of cognition has no impact or significance. It’s essential to undertake these studies since knowing how to accurately remember words is crucial, particularly in the educational system (Battig & Einstein, 1977). We ought to have two separate series of questionnaires in the future. One research examines how word retention is affected by cognitive depth, and another demonstrates whether or not we currently have a cognitive pattern.

Conclusion

In conclusion, human temporal memory and how it processes words as humans encounter them have been proven to affect our capacity to recall a word. A remembering gathering of thoughts and activities that happened at a given moment or area is known as episodic memory. The way we interpret diverse objects, like words, is called encoding. These multiple forms of information that are available are referred to as stages of thinking, whilst the degrees of semantic engagement is referred to as cognitive processes (Craik and Tulving 1972). Craik and Tulving (1972) conducted a study to see if the depth of cognition influenced how well people remembered words. The efficiency of people’s memories was predicted to change with the cognitive processes (Craik and Tulving 1972).

Craik and Tulving experimented with different degrees of decoding and assessed the quickness of the individuals’ reactions to seeing if remembering ability varied consistently with the cognitive processes. As a result, the current study concentrates on the many processes that play a role in remembering new knowledge. These methods include focusing, processing, practicing, and retrieving, to name a few. Craik and Lockart have proposed a new way of looking at human memory (1972). The study took place in an unintentional learning environment, in which participants completed a series of focused exercises that required a variety of mental processes and had an impact on learning. Individuals had a higher recall rate when they undertake various orienting tasks that require more effort in thinking and processing of the words provided to them in a question, according to the research.

It may be deduced from the data that depth of cognition had an impact on word retention in this study. The major effects of lateness, or the time it took people to enter their responses, were minor. Regardless of how much cognitive the questions needed, it did not influence the respondents’ capacity to recall the words. Nonetheless, there were significant primary drivers of correctness, suggesting that using different rates of depth analysis resulted in inconsistent accuracy in the respondents’ responses. In terms of word retention, the final data disproved the idea of cognitive processes.

References

Baluch, B., & Besner, D. (1991). Visual word recognition: Evidence for strategic control of lexical and nonlexical routines in oral reading. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, And Cognition, 17(4), 644-652. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.17.4.644

Battig, W. F., & Einstein, G. O. (1977). Evidence that broader processing facilitates delayed retention. Bulletin of The Psychonomic Society, 10(1), 28-30. doi:10.3758/BF03333537

Bentin, S., & Katz, L. (1984). Semantic awareness in a nonlexical task. Bulletin of The Psychonomic Society, 22(5), 381-384. doi:10.3758/BF03333851

Seamon, J. G., & Murray, P. (1976). Depth of processing in recall and recognition memory: Differential effects of stimulus meaningfulness and serial position. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 2(6), 680-687. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.2.6.680

Walla, P., Hufnagl, B., Lindinger, G., Deecke, L., Imhof, H., & Lang, W. (2001). False recognition depends on depth of prior word processing: A magnetoencephalographic (MEG) study. Cognitive Brain Research, 11(2), 249-257. doi:10.1016/S0926- 6410(00)00079-3