The Impact of Interest Rate Marketization on Chinese Commercial Banks

Number of words: 12307

Abstract

The research study examine the impact of interest rate marketization in China using qualitative (Interview) and quantitative research methods. The results indicated that interest rate marketization have positively impacted commercial banks as evidenced by increased operations and functions in China and in foreign countries. The findings would be attributed to the financial reforms that have been at the core of China’s economic growth and development since 1995. With an increased competitiveness of commercial banks, Chinese have taken loans at affordable rates and deposited their savings, which equally earns increased rates. Reforms executed in China could be applied in other regions of the world.

Keywords

Interest rate marketization; commercial banks; China; Financial sector, globalization

An overview of Market Oriented Interest Rate

Since the introduction of financial reforms that called for interest rate marketization, all categories of commercial banks in China, including rural, small and large financial institutions have exercised autonomy in setting interest rates for loan and deposit products (Morrison, 2019). From the mid-1970s to present, commercial banks have recorded increased growth because of favorable business climate brought about by interest rate liberalization (Chi, and Fu, 2016). In addition to providing domestic financial services, commercial banks have expanded to international markets, offering loans to countries and firms around the world (Watkins, Lai, and Bradsher, 2018). New economic reforms featured eased monetary policies that increased bank lending as well as efforts to promote domestic consumption. With banking sector being driven by market fundamental, and China opening up its doors to major markets, including the U.S, China’s economy have recorded on average double digit GDP’s growth over the past three decades (Li, and Liu, 2019). With an increased growth of bank lending, they grew in size, which have allowed banks to provide financial services in the economy sector to fund both short-term and long-term development projects (Watkins, Lai, and Bradsher, 2018). Developments contributed to employment creations, improved standards of living and eradication of extreme poverty, which explains rapid economic growth and financial stability (Herr, and Priewe, 1999). Interest rate marketization reforms implemented in China are based on economic principles of supply and demand. With the rapid economic growth, China economic reforms have emerged as an alternative route towards economic prosperity. Economists globally have developed interest in studying China’s economic roadmap, and transferring the knowledge to other developing and underdeveloped countries across the globe.

Chapter 1

Introduction

People’s Bank of China, received instruction from the ruling party, The Community Party of China (CPC) to plan for the implementation of interest rate marketization reforms in 1995 (Zhao, Wang, and Deng, 2019). These reforms were aimed at allowing commercial banks to be more autonomous (Xiao, and Zhou, 2015). Essentially, the reforms sought to permit the banks to apply interest rates on their products, which included loans and deposits depending with the rate of supply and demand (Chi, and Fu, 2016). This was a new beginning for commercial banks as government interference was significantly reduced. Interest rate marketization has been recognized as an important financial and or economic reform toward improving the degree of financial marketization in China (Li, and Liu, 2019). Interest rate marketization has been fundamental in China’s economic growth and development based on two crucial factors. Firstly, large-scale capital investments that were funded through domestic savings from the various Chinese banks contributed significantly to the rapid economic progress and growth witnessed in China (Bayoumi, Tong, and Wei, 2012). Secondly, increased Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) leading to rapid productivity growth could be traced to reforms on interest rate marketization (Morrison, 2019).

Over the past four decades following the introduction of interest rate marketization, there are specific changes noticeable in operations undertaken by commercial banks. The commercial banks initiated a deposit guarantee scheme for their customers (Xiao, and Zhou, 2015). Through this reform, customers have taken development loans from their respective commercial banks to invest in a rapidly growing economy. Comparatively, the reforms saw the removal of implicit guarantee that was previous placed on the commercial banks (Morrison, 2019). Correspondingly, deposit rates were liberalized allowing customers to not only feel motivated to save in their banks but also benefit from higher returns that come with increased savings. Besides, the removal of capital allocation controls placed on the People’s Bank of China meant that commercial banks could access finances from the central bank. Interest rate marketization has impacted China’s economic and financial growth and development in various ways. In particular, the reform has allowed commercial banks to apply market-interest rates that are more risk but more profitable compared to government-controlled interest rates (Shevlin, and Wu, 2014). Correspondingly, more accuracy and precision in financial institutions across China have been attained (Geng et al., 2016). Also, the reforms attribute to the promotion of a broad range of financial products and services offered to the customers. Ultimately, the reforms account for the current competitiveness witnessed in the Chinese financial sector between different commercial banks (Guan, Liu, Xie, and Chen, 2019).

For many years, China’s banking and the financial sector was a monopoly and dominated by a single player, the People’s Bank of China (Liang, 2017). Limitations and challenges that arose as a result of monopoly in one of the country’s critical sectors forced the government to gradually adopt and implement liberalization strategies in the financial sector (Kumiko, 2007). Interest rate marketization made it permissible for commercial banks to establish operations, launch bond markets and create a money market to determine the liquidity price (Chi, and Fu, 2016). Before the enactment of policies detailing interest rate marketization, China’s financial and economic policies were strictly under the direct control of the central government (Morrison, 2019). This meant that factors of supply and demand were overlooked as the government mostly applied rates that would have favoured its political interest and agenda. In most cases, the interest rates published by the government, under the leadership of Central Bank were ineffective and unsustainable in the long term as they did not reflect the present financial market on a global scale (Li, 2014). Equally important, government control and interference in the financial market slowed the economic progress signaling a delay in the attainment of economic goals promised by the ruling party leader, Xi Jinping (Gang, 2018).

In this research study, the researcher aims to investigate the financial market journey that China has been on since the inception of financial reform in the last quarter of 20th century. China’s transition to a market economy under financial reforms will be studied. The study aims to show how government’s role in controlling financial market declined in support for liberal reforms. Impacts of these reforms on the role of China’s commercial banks will be included in the study. Besides, whether China’s reforms provides useful lessons for other developing and underdeveloped economies is also included in this study.

Thesis Statement

Interest rate marketization have impacted commercial banks operations and functions making financial sector one of the most progressive sectors and driver of China’s economy. The study will detail how interest rate liberalization altered the role of commercial banks in the financial sector as well as the transferability of China’s reforms to other countries.

Specific Research Questions

- What is the impact of China’s interest rate marketization reforms on large, small and rural commercial banks?

- What are the implications of interest rate marketization on China’s rapid economic growth and financial stability?

- What is the applicability of China’s interest rate marketization reforms on commercial banks in developing and underdeveloped countries around the world?

Research Questions Rationale

Research questions rationale details the reasons for conducting the study. The primary purpose of the study is to present the existing outcome of the impact of market liberalization on the commercial banks operating in China. It is important to note that the commercial banks to be considered in this study would be either domestic or foreign or both. Based on the existing knowledge acquired that interest rate marketization impacts commercial banks differently, with relation to the size, it would be ideal to include three different categories of China’s commercial banks. In particular, the research question will cover rural, small city, and large commercial banks. Through the first question identified above, the study focuses on the direct and indirect impact of liberalization on active commercial banks. Essentially, this question will propel the study to investigate how the three levels of commercial banks view these reforms and responded to them in their internal working operations and tactics. We will gain an in-depth understanding of how different commercial banks attribute to loans and deposit spreads in an era where interest rate marketization has gained recognition from the international communities. We aim to shed more light and put into perspective how these reforms have contributed to the Chinese financial banking sector.

The second question is significant in demonstrating the contribution of these reforms in economic growth and financial stability currently being reported or evidenced by China. Borrowing from numerous studies conducted over the years, this question is ideal to show the correlation between reforms and progress witnessed in China over the past three to four decades. Through the reforms, the question will highlight instances where commercial banks have been at the forefront in facilitating economic growth and developments across China through increased loans and resource allocations.

The third question will put into perspective the adaptability and applicability of China’s financial reforms in the banking sector industry to other financial sectors across the globe. As indicated in the question, we will focus on developing and underdeveloped countries. Nonetheless, this does not mean that these reforms are not applicable in developed counties as well. It is a precise decision that has been taken to focus on underdeveloped and developing countries. The rationale for this decision is based on the fact that China was categorized as an upper developing country when it launched these reforms over three decades ago.

Theories of Economics

Two theories of economics by Irving Fisher and Laissez-Faire will be used to base arguments. On the one hand, the Fisher Effect economic theory by Irving Fisher states that the real interest rates amounts the nominal interest rate subtracted the expected inflation rate (Tymoigne, 2006). This theory has limitations whereby economic prosperity, confidence and prices of assets tend to rise, rendering interest rates ineffective in reducing demand. This is defined as elasticity of demand to interest rates. On the other hand, Laissez-Faire theory argues that the, “less the government is involved in the economy, the better the business will be, and by extension, society as a whole” (Hill, 1964). The fundamental beliefs behind this theory is that competition constitutes a “natural order” that drives how economy runs. The aspect of “natural order” indicate that the government has limited to no roles in interfering with businesses and industrial affairs. This theory criticizes and disapproves any type of legislation or oversight by the government, which includes but not limited to interest rate regulations, corporate taxes and trade restrictions. These theories will be applied to base arguments on China’s interest rate liberalization reforms.

Chapter 2

Review of the literature

A comprehensive review of the literature, case studies, article journals, newspaper reports and other reputable sources related to interest rate marketization in China and the underlying impact on commercial banks will be included in this review. An assumption that the impact of reforms were evident after 10 years since the inception in 1995 will be applied. This is to mean that materials to be considered fit for this research would have to be published from 2005 and beyond. This represent the criteria to be applied for inclusion and exclusion of resources. A detailed comparison to show the similarities and differences as reported by different researchers will be provided to help in guiding the direction of the study. It is important to note that literature review is treated as secondary data that will be compared with primary data to be collected to show correlation of the issue at hand.

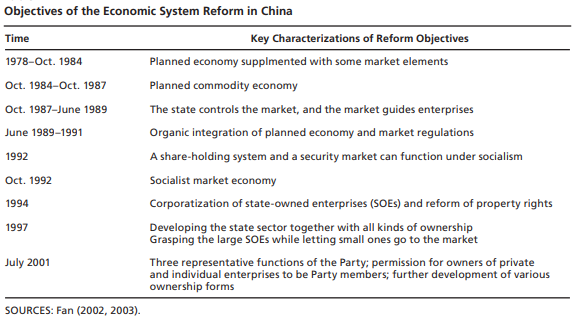

2.1 Literature on Financial Sector Prior To the 1995 Financial Reforms

To understand the impact that interest rate marketization had in commercial banks’ financial performance, it is worthwhile to recognize how the China’s financial market fared before the reforms were introduced and after. Kumiko, (2007) point out that the economic framework used before the 1995 reforms had two distinct characteristics of banks loans being heavily weighted towards funding the non-financial sector and the banking sector being dominated by state-owned commercial banks and joint stock commercial banks (Herr, and Priewe, 1999). While there lacks no standard balance between direct and indirect finance, it has come to be understood that an unbalanced financial system tend to result in retard efficiency of fund allocation. Gang, (2018), notes that commercial banks in China were overburdened under the reforms, which had degraded their balance sheets making it almost impossible for the banks to offer loans (Zhao, Wang, and Deng, 2019), to some of the profitable businesses sectors at the time. This is in agreement with Kumiko, (2007) analysis that revealed that China’s had unbalanced financial system before 1978 reforms. While the reforms introduced in 1978 lacked clearly defined goals, the reforms were focused on moving China from the “planned economy (Boyreau-Debray, and Wei, 2005) supplemented with some market elements to the socialist market economy”, gradually becoming more aligned to market-oriented framework (Kumiko, 2007).

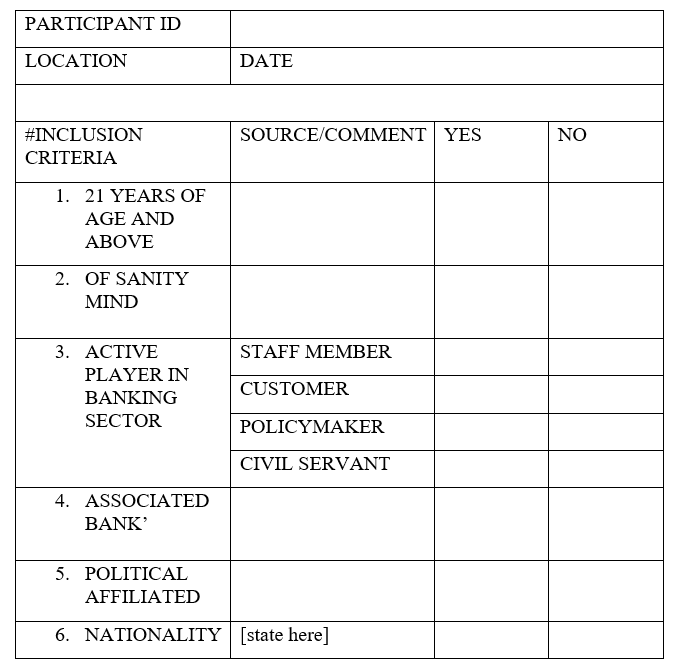

Figure 1: China’s Economic System Reform

Before 1978, the Chinese banking system would have been considered a soviet-style single banking system (Kumiko, 2007), under the control of central government (Morrison, 2019). It was during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) that financial institutions were either closed or incorporated into the PBC or the Ministry of Finance (MOF) (Kumiko, 2007). At the start of mid-1970s, the central government made attempts to strengthen the role of the PBC after it was separated from MOF to function as a bank. Although the central government continued to control the PBC, it is evident that this was a great move in restoring the financial system (Quintyn, Laurens, Mehran, and Nordman, 1996).

From 1978 until 1984, additional reforms were enacted where the four state owned specialized banks were separated from the PBC, and each bank allocated a particular function (Shevlin, and Wu, 2014). The Agricultural Bank of China (ABC) was assigned the role of financing the rural and agricultural sectors. The bank of China (BOC) was assigned financing investment and foreign trade. The People’s Construction Bank of China (PCBC), later renamed the China Construction Bank (CCB) would finance the construction and fixed asset investment. The Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) was assigned the role of financing the business activities of the SOEs (Kumiko, 2007). These four institutions relieved the PCB its role as the only commercial bank. With clearly defined roles, competition in commercial banks emerged in the mid-1980s. With each bank focusing on specific areas, it occurred that interest rates on loans provided by each of the institutions would not be standard (Liang, 2017), considering economic dynamics. While the reform was effective, there was a missing link on how interest rate would be adjusted to reflect on the component of supply and demand of each sector (Chi, and Fu, 2016).

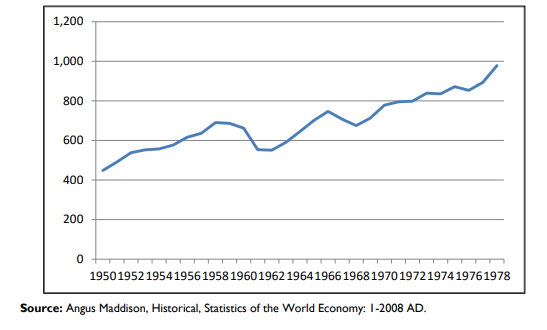

Based on Chinese Government Statistics, China’s GDP grew at 6.7% on average annually from 1953 to 1978 (Morrison, 2019). While the accuracy of these data has been questioned by experts, it is clear that growth was below ten percent. Boyreau-Debray, and Wei, (2005) argued that Chinese government often overstated production level for political reasons, which explains the constraints of a state-controlled financial system (Zhao, Wang, and Deng, 2019). An analysis conducted by an independent economist, Angus Maddison contradicted the government records. According to him, China’s economy grew at 4.4% on average annually, from 1953 to 1978 (Morrison, 2019). Prior to 1979, a larger share of economic output was under the direct control of the state, which set production goals, allocated resources and controlled prices (Shevlin, and Wu, 2014). It was during the leadership of Chairman Mao Zedong that the state launched large-scale investments in both human and physical capital. Morrison, (2019), about 75% of industrial production was under state-owned enterprises in 1978. With limited autonomy in the country, private enterprises and foreign invested businesses were not motivated to join the sector (Kumiko, 2007). Government often barred private and foreign businesses in efforts to make China’s economy relatively self-sufficient (Morrison, 2019). There was no market mechanism in place to ensure resources are allocated efficiently (Kumiko, 2007). As such, China offered few incentives for workers, farmers and firms to motivate them into increasing production or promoting quality of the products.

Figure 2: Chinese Per Capita GDP: 1950-1978

($ billions, PPP basis)

In the figure above, China’s per capita on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis doubled from 1950 to 1978 (Morrison, 2019). Nonetheless, living standards dropped in some of the years, highlighting the inefficiency and challenges of a financial sector that is under the control of a central government (Herr, and Priewe, 1999). In these years, Chinese government had not thought of commercial banks as financial institutions with major impacts on the financial market. The death of Mao Zedong opened new debates among financial experts and economists, as well as policymakers about the reforms that China would take to ensure sustained economic growth (Zhao, Wang, and Deng, 2019).

In closing, Chinese financial market prior to 1978 was under the direct control of the central government. Unaccommodating policies that barred private enterprises and foreign investors explains the stagnating economic growth of less than ten percent from 1950 to 1978. The next section will discuss the implementation of market-oriented interest rates starting 1979 as undertaken by the commercial banks.

2.2 Role of Commercial Banks in the Implementation of Market-Oriented Interest Rates

Since China introduced interest rate marketization reforms, scholars, researchers, policymakers, and economists both in China and around the world have been devoted to understand the economic progress that could be traced back to China’s financial reforms of 1995 (Huang et al., 2013). Efforts have been propelled by the continued attempts to investigate, understand and raise awareness about the impact that the reforms have had on Chinese commercial banks. Introduction of four bank institutions to replace the PBC was the first stage of financial reform which changed the functions of commercial banks (Quintyn, et al., 1996). In the second stage that occurred from 1993 to 1997, market-oriented policies were implemented in what was termed as large-scale experimentation with financial market. The gradual reforms saw the role of central government in financial sector diminish gradually Meng, et al., (2020). Key financial reforms including the establishment of a liberated macro-economic control mechanism by the PBC, and the formation of policy banks marked a gradual change in the financial market (Bell, 2013). Comparatively, state-owned specialized banks were transformed to commercial banks (Herr, and Priewe, 1999). Also, a unified, open, well-ordered and managed, as well as competitive financial market (Xiao, and Zhou, 2015) was established under the new reforms.

Equally important, financial service infrastructure were developed leading to the establishment of a modern financial-management system in China (Shevlin, and Wu, 2014). Although these reforms directly impacted the commercial banks, the researcher overlooked the actual impact of interest rate marketization on the four commercial banks (Meng, et al., (2020). Lack of empirical evidence on how effective or ineffective the reforms were in making China the second world’s largest economy after the United States highlight weakness of the study (Clark, and Monk, 2011). While the reforms could be attributed to China’s progress in eradicating extreme poverty within the shortest time possible in history (Li, and Liu, 2019), the study does not clearly show how increased autonomy by commercial banks via interest rate liberalization accounted for improved financial market (Chi, and Fu, 2016).

Cui, (2016) claims that interest rate marketization and liberalization have been the major determinant in China’s economic growth and financial expansion. Arguments presented revealed that the reforms introduced in the financial sector positively impacted commercial banks as they were allowed to restructure their internal interest rates formulas (Chi, and Fu, 2016) to best suit their customer’s needs as well as organizational goals and objectives. With the role of central government in the financial sector gradually diminishing, (Li, 2014), commercial banks took over crucial functions to adjust interest rates on loans offered to businesses (Chi, and Fu, 2016).

Interest rate marketization reforms that were put in place allowed commercial banks to increase credit risk (Cui, 2016), which resulted in an increased customer base as more customers could acquire loans (Kumiko, 2007). The independence of commercial banks an increased role of stakeholders in decision making process. Establishment of the four commercial banks, with each focusing on specific area contributed to fundamental changes on how interest rate would be determined (Shevlin, and Wu, 2014). As the economy improved, commercial banks continued to play more increasingly roles in decision making (Chi, and Fu, 2016). Unlike in pre-reforms period when the central government controlled the financial sector, the reforms provided commercial banks with an authority to set interest rates that reflected supply and demand. Gang, (2018), globalization impacted financial market in nearly all countries, subsequently requiring major economies, like China to make adjustments to its financial sector. Although credit risk is the greatest costly risk in financial institutions because it directly threatens the solvency of financial institutions, commercial banks provided loans to individuals and businesses at competitive rates (Guan, Liu, Xie, Chen, 2019). Economic trends that had been witnessed in China were encouraging, more people were climbing up the socio-economic ladder while businesses thrived nearly in all sectors (Li, and Liu, 2019). Economists predicted that China would record double digit economic growth under the new reforms (García Herrero, and Santabárbara García, 2004). On average, China has been able to double its GDP every eight years (Li, and Liu, 2019). The World Bank pointed out that, “China had experienced the fastest sustained expansion by a major economy in history.” (Morrison, 2019)

Xiao and Zhou (2015), noted that a single asset and liability arrangement was being used by China’s commercial bank. In their findings, China’s deposit and loan businesses are not aligned, making interest income is the country’s primary source of revenue from the banking industry. With the liberalization of interest rates, loans and deposits became the main assets and liabilities for the commercial banks (Xiao and Zhou 2015). Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) (1970) by Fama holds that in an efficient market, stocks tend to trade at their fair market value in the security exchange, thus reflecting the actual performance (Warue et al., 2018). Under this kind of transparency, investors are more empowered, thus make informed decisions. Commercial banks were involved in setting competitive interest rates, which, allowed them to attract huge customer base and earnings. Cui (2016) agrees with Warue et al., (2018) that Commercial banks’ ability to adjust interest rates on loans and deposits pulled more customers. Besides, the reforms allowed commercial banks to either increase or decrease interest rates on loans taken by their customers. In a study conducted by Xiao and Zhou (2015), it was evidenced that the rate of interest rates placed on products decreased from 6.1% to about 3.01% from 2007 to 2012. The decrease in interest rates on various products offered by the commercial banks represents increased power at the hand of commercial banks that was initial controlled by the central government (Herr, and Priewe, 1999). In the same period, banks were able to attract a larger customer base by offering highly competitive products. Similar findings were presented by Cui, (2016) whose findings indicated that the reforms came with some degree of freedom as commercial banks starting involving themselves in high-risk projects because of the high interest rates associated with projects of such magnitude.

Similar findings by Geng et al., (2016) was that competition between commercial banks was rooted in the financial reforms that allowed banks to independently price their products so as to gain a competitive advantage over the rivals. The marketization of interest rates in China gave commercial banks easier access to capital pricing and also a major opportunity to take major market risks with higher returns (Xiao, and Zhou, 2015). Comparatively, these reforms account for higher efficiency in resource allocation to both domestic and foreign investors. Under interest rate marketization, Chinese corporate savings and household savings have increased considerably making China to be ranked among the world’s leading economies (Zhang et al., 2018). Unlike previous when China’s financial sector reforms were under the control of the central government, the financial and economic restructuring plans that were introduced under the interest rate marketization have allowed China’s economic and financial sector to be hybrid as opposed to being centrally controlled (Xiao, and Zhou, 2015).

Shevlin and Wu, (2014) noted that interest rate marketization reforms that were launched by China over 4 decades ago have been instrumental in the country’s commercial banking sector. As presented in the study, commercial banks in China have established operations and initiatives that were once only permissible for the People’s Bank of China before the introduction of major financial reforms in 1995 (Huang et al., 2013). Comparatively, findings from this study revealed that the role of commercial banks in pricing the interest rates to be provided signaled increased risks on the banks but more profitability. Similar findings of freedom of commercial banks to price loans and deposits were observed by Meng et al., (2020).

Interest rate marketization reforms showed that China had been a sleeping giant all along. At domestic level, reforms brought about rapid economic growth, with commercial banks facilitating the progress. In the next section, I will discuss how the reforms have contributed to the current status of numerous Chinese commercial banks as global financiers.

2.3 Chinese Commercial Banks in the Global Financial Market

China’s overseas development policy has been termed debt-trap diplomacy owing to the huge loans that China’s commercial banks have offered to countries around the world. The Asia Focus indicates that China’s interest rate liberalization plan of 1995 saw the removal of all restrictions on bond market rates and money market rates. Interbank lending, financial institution bonds, and central government bonds were allowed to be fully priced based on the existing market (Li, 2014). It is such reforms that contributed to deregulation of the China’s bank deposit rates and lending in later years. A decline in interest rates, allowed the banks and customers to take loans amounting to billions of dollars to undertake mega projects not only in China but in other regions around the world. Mostly, projects are concentrated in regions that China has interest, notably Australia, Kenya, Djibouti, Zimbabwe, Sri Lanka and Pakistan (Korniyenko, and Sakatsume, 2009). Commercial banks are fueling the world economy on a scale not seen before. Commercial banks offer competitive interest rates on loans to fund the projects. The stock of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in China has gradually grown from 1992 reaching an all-time high in excess US$45 billion per annum between 1996 and 1998 (Korniyenko and Sakatsume, 2009). As indicated, China became the second largest recipient of FDI after the United States in 1996. With over 2000 joint ventures and wholly foreign-owned enterprises in China, commercial banks were instrument in ensuring smooth operations (Watkins, Lai, and Bradsher, 2018). The investment saw about 18 million people secure job in different sectors, which accounted for over 2.5% of the total employment. Commercial banks based in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Macao and the United States contributed 48.8 per cent, 8.2 per cent, 3.1 per cent and 8.2 per cent FDI, respectively while Korniyenko and Sakatsume, (2009) reports the stock of Chinese FDI abroad increased from US$ 75.0 billion in 2006 to US$ 117.9 billion in 2007.

In an article published by the New York Times, China’s commercial banks have financed nearly 600 projects around the globe releasing billions of dollars in loans, investments and grants (Watkins, Lai, and Bradsher, 2018). The Belt and Road initiative has been involved in infrastructure projects in over 112 countries. This could be explained by Cui’s (2016), findings that showed that commercial banks in China developed robust intermediary businesses due to increased deposits from their customers. As banks provided favoured interest rates that were based on supply and demand, economists in China encouraged people to rely on the banking system for financial freedom through increased deposits and loans applications. On the same token, increased in financial assets held by the commercial banks in China allowed them to venture into other businesses other than being over-reliant and dependent on deposit and loan spreads. As commercial banks recorded increased revenue, their contribution to the national government through taxation also increased proportionately.

2.4 Financial Market during Interest Rate liberalization

Scholars such as Meng, et al., (2020) believe that the advancement in interest rate liberalization that was undertaken by China attributes to the gradually narrowing of loans and deposit spreads in commercial banks. This could be considered a positive trend towards harmonizing the value of loans and deposits. For many commercial banks, the interest rates on loans tend to be higher than that of deposits. This could discourage people to save as they feel that the bank is dishonest and greedy as well. With a narrowed loans and deposit spread, customers were motivated to save and equally take loans with their commercial banks.

Meng, et al., (2020) cited that the income structure and profit levels for the commercial banks have been impacted either positively or negatively, concerning the competitiveness of any given commercial bank. In his finding, the initiation of interest rate marketization resulted in volatility narrowing of net interest of the commercial banks. Nonetheless, the competitiveness index indicated a significant increase in competition by China’s commercial banks to lend loans to an increasing customer base. Small and medium enterprises, large corporations and organizations, and more people could access highly competitive loan products and services.

In a study conducted by Guan, Liu, Xie, and Chen, (2019), the dynamic evaluation score by the five most competitive commercial banks between 2013 and 2017 included Industrial Bank, China Merchants Bank, Shanghai Pudong Development Bank, China Construction Bank, and Agricultural Bank of China. On the other hand, the bottom five banks, herein considered uncompetitive included Bank of China, Ping An Bank, China Minsheng Bank, China Everbright Bank, and CITIC Bank. From this finding, the competitive nature of China’s commercial banks is evident, which implies an increased profit margins. While some of the state-owned banks like China Construction Bank and the Agricultural Bank of China were profitable, there were not as competitive as non-state banks (Guan, Liu, Xie, and Chen, 2019). As an example, the profitability level of the Industrial Bank was higher than that of China construction bank. It could be argued that people were more interested in working with non-state banks as they assumed that government interference in state-owned bank was higher than in private commercial banks. Meng, et al., (2020) and Guan, Liu, Xie, and Chen, 2019 findings correlates in that the commercial banks were permitted a larger scope to internally price loans, which, in turn, prompted fierce competition in the banking sector between the different commercial banks.

Meng et al., (2020) found that the reform lowered the entry requirement and removed some of the barriers that prevented foreign bank commercial banks from venturing into China’s financial market. In other words, interest rate marketization allowed foreign commercial banks free entry and exit to and from the market without incurring heavy financial consequences or implications. In the effort to attract more clients, most of the commercial banks, especially the foreign banks were forced to lower their interest rate or could not increase it without adequately engaging the stakeholders (Li, and Liu, 2019). Results presented in the study pointed out that limited government involvement in the control and regulation of interest rates allowed investors and other external players’ entry into the financial market aiming to realize profits from the revamped and lucrative banking sector.

According to Asia Focus, the impact of interest rate marketization has varied for the Chinese commercial banks depending on income sources, asset size, and management strength, and existing business strategies (Li, 2014). The author noted that the differences in sizes among the commercial banks including large commercial banks, mid-sized joint-stock commercial banks, and small city and rural commercial banks account for the different challenges that each of the able banks is bound to face in the wake of interest rate market liberalization. As stated therein, about 5 of the largest Chinese commercial banks controlled about 40% of assets of the banking financial sector (Li, 2014). Given that interest rate marketization weighed on profitability, it was the small and rural commercial banks that were largely impacted by the reforms (Clark, and Monk, 2011) as large commercial banks faced limited negative impacts in a highly competitive market. As stated, stable customer relationship enjoyed by large commercial banks was an insulator following the implementation of the reforms. For the small city and rural commercial banks in China, interest rate marketization brought greater challenges as such banks were sensitive to liquidity risks and funding, hence susceptible to market volatilities (Li, 2014). Even with interest rate liberalization, such banks were characterized by a limited branch network that disadvantaged them when competing for retail deposits with large commercial banks (Xiao, and Zhou, 2015). In an article by Li, (2014), published by Asia Focus publication, China has made significant progress in the last two decades since it embarked on interest rate marketization reforms. The removal of the deposit rate ceiling has been identified as a major step that allowed China to develop economically and grow financially to attain its current economic status as the second-largest world economy (Clark, and Monk, 2011). As indicated in the article, a growing global consensus among world-leading policymakers and financial experts is that interest rates should be determined by market forces (Li, 2014). He believed that China was able to ride on this knowledge as evidenced in its 1995 financial reforms that culminated in interest rate marketization. Interest rate marketization led to a widening of credit access to sectors that were previous considered undeserving and more efficient allocation of financial resources (Guan, at al., 2019). Besides, the reforms promoted sustainable economic growth that supported the business community across China (Hou, Wang, and Zhang, 2014).

The relationship between banks’ behavior and financial business among the small firms has attracted considerable attention in the recent years. Many scholars have studied the relationship as evidenced in different countries around the world. To put China’s case into perspective, a research study was conducted in Zambia from 1980 to 2005 reported that interest rate marketization positively impacted the lending and deposit rates in commercial banks. Guan, at al., (2019) found that S & P rating standards of 1999, four major commercial banks had attained credit worthiness, thus attracted investments form domestic and foreign investors. S&P rated the following: Bank of China (BB+), China Construction Bank (BB+), The Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (BB+) and China Bank of Communication (BB). As per S&P ratings, any commercial banks rated BB and below would be considered not credit worthy, thus do not attract customers (Guan, at al., 2019). Based on the findings, it could be interpreted that the fact that most of the commercial banks in China had attained credit worthiness, interest rate marketization had created a positive trend and financial growth.

Chapter 3

Method and Design

Mixed Research method

A mixed research method by integrating both quantitative and qualitative research methods was conducted. Subjects included in the research study were selected from various sub-sectors in the banking sector, and they included four bank officials, business owners or entrepreneurs, individual customers, companies’ representatives and policymakers. All these participants are key stakeholders in the banking sector. As such, they should be able to provide incredible insights about the impact of interest rate marketization on the economic sector. Based on the nature of the research, it proved ideal to use available resources and materials so as to dive deeper into the research topic. As it would be noticed, interest rate marketization is a dynamic element that changes as influenced by the factors of supply and demand. On the one hand, the quantitative research method will entail the review and analysis of reputable research studies related to the topic. Additionally, case studies conducted on the interest rate marketization and its impact on China’s commercial banks was included in the study. Specifically, materials published from 2005 to 2020 were have been included in the study.

Assumptions

The impacts are expected to be all inclusive, in that impacts should be felt at banking financial strength and growth over the years, especially between 2005 to recently, preferably 2020, at individual level in that the number of people in different social classes including low, middle and high classes will have positively charged over the years. This is to mean that the more people will have moved from low class to middle class within the provided timeline. Also, the number of people in the middle class would have shifted to the high class as evidenced by improved living standards across China. It is assumed that the banking sector contributions in terms of taxations will have doubled between 2005 to pre-Covid-19 year, 2018.

Data Collection

The researcher applied the Qualitative research method of interview technique to collect information and data useful to the study from the participants. Judgment (or purposive) sampling method was used to select participants. The participants were strategically selected to suit the needs of the study, owing to the fact that these participants were key stakeholders in the banking sector. Judgment sampling was selected as it is cost and time effective. Additionally, it results in a wide range of responses that allows the researcher to make valid conclusions. However, this method is characterized by volunteer bias of the researcher’s judgment. Also, the participants and the findings might not be representative.

Participants included in the research study were three bank executive management staff, two entrepreneurs acting as banks customers’, three individual customers and three policymakers. In line with the current COVID-19 restrictions that state people should stay at home and avoid close contact with others, interviews were held virtually as outlined in the Gannt Chart provided. Technology was pivotal in this research study was it was the primary point of interaction between the researcher and the subject. Tools that were at the disposal of the researcher and the subject would be selected and agreed upon by the two parties. For all the interviews that were held, Zoom and Skype were used to connect the researcher and the subject. It is important to acknowledge that virtual interviews were held comfortably, though we experienced poor internet connection in two cases. For the two cases, only responses that were audible were considered as fit. In addition to the interviews, the participants were required to fill a questionnaire that included 15 questions. All participants send back filled questionnaires. To promote confidentiality, participants were not expected to include their names in the questionnaire. While another question about confidentiality emerged as to how using email compromised confidentiality, the researcher used a third party to open the responses on his behave. The researcher was only provided with printed responses. The data collected was compared to the interview findings as it is revealed in other sections of the study. Secondary sources such as articles, journals and research studies have also been included in the study. data collected from these sources would be compared with that collected during interviews to show its credibility and reliability.

Participants

As mentioned earlier, Judgment sampling method was applied in selecting the participants. Three executive management staff from China Merchants bank, Bank of Shanghai and Harbin Bank were included in the study. To identify and select these participants, the researcher made appointments with the bank corporate managers and requested for the staff members to be permitted to contribute to my study. Additionally, five individuals, herein considered reliable bank customers with at least 20 years as active customers in a commercial bank operating in China is hereby considered as a potential subject. The five participants were randomly selected from civil servants and customers’ with accounts in the named commercial banks. In line with the research questions outlined above, I selected participants that represent all three categories of commercial banks. Three representative of businesses or companies with ties to the commercial banks, and have taken loans or deposited their finances in these commercial banks since 2005 were included in the research study. Lastly, policymakers that have been part and parcel of the reforms and have witnessed China’s rapid economic growth were included in the study. In particular, a politician, an economist, and financial analyst were included in the study.

Inclusion & Exclusion Criteria

Individuals to be considered in the study were active players in the banking sector. In particular, one had to fall under the following areas, banking staff member, bank customer (individual or as an entrepreneur), policymaker, and civil service. It was a requirement that each participant be over 21 years of age and of sound mind. More details about the inclusion and exclusion criteria is included in the appendix section. Both and Female had equally chances to participate in the research. The researcher ensured 2/3 gender role when selecting the participants. Individuals considered to be politically manipulated like the proponents of CPC and hard critics of the government were also excluded from the researcher. In researcher’s view, the credibility and reliability of the data collected would only be promoted by limiting the number of ‘compromised’ individuals.

Ethical Considerations

APA’s Ethics Code that mandates the manner in which research study involving human subject ought to be carried out was followed during the study. As such, I provided the participants with a written consent form as required by Ethics and Review Board or any other regulatory bodies. Details captured on the consent form included the purpose of the study, timeline and procedures that would be observed, participants right to volunteer or decline or withdraw from the research at any given time, and the underlining consequences of such actions. Confidentiality was guaranteed when reporting the findings collected during the study. The researcher was conscious of the multiple role and interactions with participants which would have impaired the professional performance or led to exploitation of participants. While the participants to be included were purposively selected, participation was on voluntarily basis.

Data Analysis

In data analysis, the researcher will apply both logical and statistical techniques to comprehensively describe the scope of data, modularize the data structure, evaluate statistical inclinations, illustrate the findings in graphs, and tables to derive meaningful conclusions and recommendations.

Significance

The research proposal is an extension of an already existing literature work that has been presented on the topic. Also, the research will address the existing gap in the topic of how reforms have affected commercial banks with operations in China. Through this research, the research will contribute to the existing knowledge capacity and further expound on it. The study will be funded through personal means, signaling no conflict of interest or any possibility of the researcher being biased while undertaking the research study. It is expected that scholars, researchers, students, and the general public will benefit from this research study and consecutively gain an understanding of the topic under research.

Chapter 4

Empirical section

4.1 Emergence of market-oriented interest rate regime

The main argument of this section is financial reforms on interest rate marketization positively impacted the banking sector. Liberalization of interest rate has contributed to autonomy of China’s commercial banks. For more than 20 years, interest rates charged on all financial products offered by commercial banks have been based on principles of demand and supply (Tan, Ji and Huang, 2016). This shows that the role of commercial banks have changed over the same period.

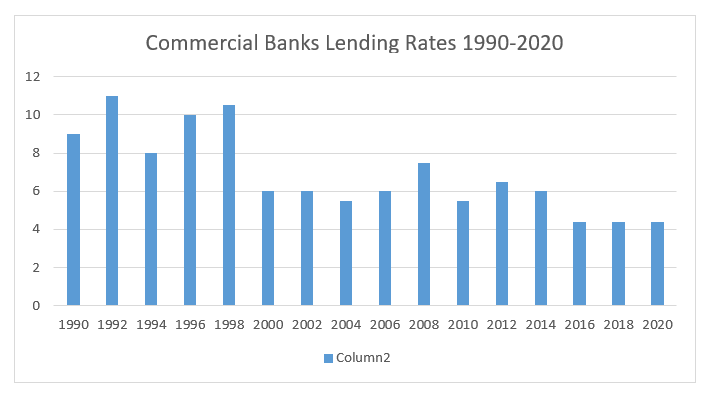

The empirical basis for this argument is commercial banks played a crucial role in the implementation of liberalized interest rates reforms. The reforms broadened the capacity at which banks operated. According to one of our participants, Mr. Lui, who is a banking manager in one of the banks, reforms that were introduced in the financial sector paved the way for a stable and usable market-driven interest rate regime to emerge. In his view, changing from price and market-based controls have been more effective than the government controlled regulations. It is through the market-oriented interest rate regime that the banking sector has been impacted significantly by administrative and quantitative steps. Similar views were echoed by Miss. Ping, an entrepreneur with over 40 years working in the construction industry and having relied on commercial banks to fund her mega projects in and outside China. To relate this, Wong, and Poon, (2011), indicates that interest rates offered by commercial banks are considered liable, contributing to a growing customer base. The graph below shows the interest rates variations over a period of 20 years. As noted, interest rates have been almost steady when set by commercial banks.

China Bank Lending Rate, 1988 – 2021 Data. Ceicdata.com. (2021). Retrieved 25 May 2021, from https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/china/bank-lending-rate.

The theoretical argument is interest rates marketization have contributed to autonomy in the banking sector, giving banks authority to determine interest rates. Based on Laissez-Faire theory, the element of autonomy reveals lowered government involvement in regulating interest rates (Yang, 2015). Rather, commercial banks in China applies factors of demand and supply in determining market-oriented interest rates. The autonomy to set interest rates have been impactful on commercial banks, the rates have not been stable (Hua-yu, 2006). This is explained by the factors of supply and demand that influences global financial markets. Limited government interference on financial sector allowed more people to gain trust in commercial banks as their financial partners (Li, 2019). Through this, the role of banking sector have changed over last 20 years.

4.2 The “Golden rule of interest rates” and its implications

The main argument is economic trends witnessed in China certifies the golden rule of interest rates. This is because China’s benchmark one-year lending and deposit rates have consistently been lower than the country’s nominal annual GDP growth rate (Liu, 2018), making borrowing affordable to customers. Okazaki, (2017) supports this in his statement that as more people turned to the commercial banks for financial support, banks grew significantly, accumulating wealth and power.

Positive implications

The empirical argument is marketization of interest rates impacted commercial banks, which is reflected on positive economic growth. Mr. Yen, a bank manager working with the Bank of Shanghai for over 20 years noted that commercial banks offer services at competitively services low rates, allowing more people to borrow and invest in the economy. As such, Wu, (2007) pointed out that China’s GDPs have gradually grown since this reforms were enacted. High inflation has resulted in negative real rates, making borrowing more affordable (Liu, et al., 2020). Although China’s financial boundaries have become more porous, institutional remaining cash balances continue to rise (Liu, et al., 2020).

Institutional investors also have a diverse portfolio of investments. Besides, there are diversified service providers, extensive service coverage and a high financial service penetration level (Dong, et al., 2016). Unlike previously where it was only the selected few or rich who had access to financial services, the reforms brought significant progress whose impact is felt at the grassroots level. Financial inclusion was in pursuit of financial wellbeing for people in the low-income category, farmers and SMEs (Fungacova, and Weill, 2014), thus creating a unique and sustainable development path. The reform emphasized MSEs low-income urban people, rural residents, the poor, the disabled and the elderly to be targeted in the financial inclusion (Fungacova, and Weill, 2014). Similar echoes were presented by participants who stated that commercial banks have recorded growth in total assets due to conducive business environment.

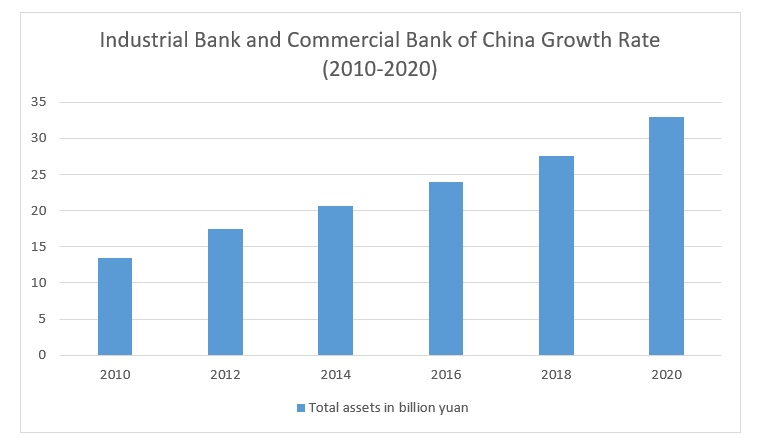

To illustrate the growth rate by commercial banks, a graphical representation is provided below. Total assets grew from 13.4 billion yuan in 2010 to 33.0 billion yuan in 2020, which represents more than 100% growth.

Negative implications

Under the new reforms, banks gained more autonomy resulting in income gap between the poor and rich had grown over the period of economic development (Ma et al., 2018). In an interview with Mr. Jo Yong’ an account holder in Harbin Bank for over 20 years, increased autonomy on the part of the bank allowed individuals to gain financial powers that even influences the political arm.

The theoretical argument is banks have become more aggressive in terms of services offered, and customers portfolio. With respect to the Fisher Effect theory, Chinese commercial banks have become more aggressive in determining the interest rates offered to their customers based on existing economic realities of nominal interest rates and the expected inflation rates (Machobani, Boako, and Alagidede, 2017). In the wake of interest rate marketization, commercial banks were primary beneficiaries. The reforms improved the availability, satisfaction and quality of financial services and products offered to the Chinese people (Li, and Liu, 2019). However, the poor become politically ignored by the ruling party, making them more vulnerable to atrocities and injustices that the government (Roubini, and Sala-i-Martin, 1992).

4.3 Chinese Commercial Banks Transition from Domestic to Global Financial Market

The main argument in this section is reforms significantly contributed to commercial banks based in China expand beyond domestic market to the global financial market. This is supported by Rolland, (2017), observation that China’s commercial banks have been able to help the BRI initiative by lending to major Chinese companies on a domestic basis, who in turn provide foreign investments in China’s strategic locations.

Domestic Contribution

My empirical argument in this section is interest rate reforms allowed banks to develop domestically, spilling over accumulated wealth through FDIs (Zhang at al., 2018). According to one of the participants, private investors are encouraged to join the banking or financial sector in order to help Chinese in rural places. Most of the reforms that have been impactful in rural areas were implemented from 2007 onward (Chen, Poncet, and Xiong, 2020). Based on the analysis that was conducted on the questionnaire issued during to the participants, it emerged that the China Banking Regulatory Commission provided various regulations and institutional framework for the setup of new village banks as well as loan companies. As rates were determined by the banks, with respect to the aspects of supply and demand, people in the rural areas were offered affordable loans (Fungacova, and Weill, 2014). According to Morrison, (2019) commercial banks engaged in diverse economic activities, including agricultural and farming activities. In his observation as a key player in the financial sector, several milestones in China’s banking reform have been achieved over the last 11 years. As a bank manager, Mr. X noted that China has also taken steps to reform its banking system, including opening of its banks to investors.

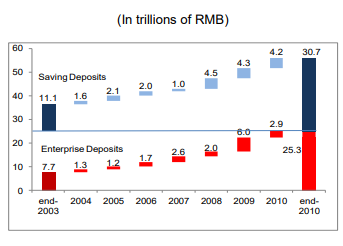

Figure 3: Levels and Incremental Growth of Commercial Bank Deposits

Finding showed that remarkable accomplishments had been made in the reform of large-state owned commercial banks. Based on the graph presented above, commercial banks savings deposits increased from 11.1 RMB trillion to 30.7 RMB trillion in a span of seven years between 2003 and 2010. In efforts to support ‘loans for government grants’ reform, it was revealed that the central government considered the establishment of various state-owned commercial banks. This resulted in the gradual discarding the division of work among the state owned commercial banks, split off the policy that touched on their businesses portfolio and transformed the banks into competitive entities alongside other players in the financial market (Chang et al., 2018).

Under the financial reforms, the power of state-owned banks and government-linked businesses at bay, therefore promoting private players to join the lucrative business. Apart from issuing bonds, banks assisted BRI ventures by serving as brokers in the RMB bond market for BRI borrowers, states, and businesses around the world, as well as issuers on the RMB bond market (Gang, 2018). Economic growth recorded in China has spilled over to other countries around the world.

Theoretical argument in this section is reforms taken by China government to promote autonomy in the banking sector follows Laissez-Faire theory that calls for limited government involvement. As government became less involved in financial matters, especially that pertains interest rates, evidence of mega project that China based financial institutions and construction companies are funding at a global level including in Africa, Asia, Middle East and Latin America that are funded by commercial banks from China (Kim, and Xin, 2021) highlight China’s commercial banks as global actors. Countries including Zambia, Kenya, Pakistan and South Africa have been destination for China’s FDI. Many commercial banks engage in market competition and jointly decide the interest rate under the marketization of interest rates condition of supply and demand. Banks’ success can be determined in part by their ability to price funds correctly and reasonably.

4.4 Favorable Interest Rates and Foreign Investments

Main argument in this section is that Chinese commercial banks have become a global player due to favorable interest rates that commercial banks and state-owned banks place on their products. The People’s Bank of China has kept the interest rates at record low level of 4.35 per cent (The People’s Bank of China, China Financial Institute, 2019). Creation of Targeted Medium-Term Lending Facility (TMLF) to finance SMEs at fovourable 3.15 per cent interest rates has significantly contributed to increased borrowing and growth of SMEs sector (Funke, and Tsang, 2021). In 2018, interest rates for large and SMEs averaged 5 per cent narrowing to 0.1. This indicated declining cost of financing SMEs. Furthermore, the China Banking Regulatory Commission established the removal of unreasonable charges, clean up and standardized extra service fees (China Banking Regulatory Commission, 2017). While Chinese commercial banks have historically restricted themselves to major financial centers such as London, New York, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Tokyo, after the reforms were enacted, a rush of Chinese enterprises and commercial banks has swept the globe over the past two decades (Kim, and Xin, 2021).

The empirical argument in this section is China’s trade and investment reforms, and incentives resulted in an increase in FDI. Credit conditions have generally improved over the past two decades through favorable interest rates, evidenced by lending rates, loan fees, the interest spread, and other indicators (“People’s Republic of China | Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2020 : An OECD Scoreboard | OECD iLibrary”, 2020). Favourable interest rates have been crucial to the provision of financial resources. Market-based interest rates account for optimization of resources allocation (Kumari, and Sharma, 2017), in both domestic (large and SMEs) and foreign investments. Between 2009 and 2018, China has implemented a series of policy adjustments, including a sole credit allocation plan, and differentiated reserve ratio policy, which aimed to encourage financial institutions to expand credit facilities (“People’s Republic of China | Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2020 : An OECD Scoreboard | OECD iLibrary”, 2020).. The National Financing Guarantee Fund has further improved lending rates to Chinese SMEs reaching an annual CNY 140 billion. According to Mr. Li, an assistant manager at the Industrial Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) from 2007 to 2009, commercial banks in China accumulated wealth that allowed them to provide foreign investment. He also noted favourable interest rates as a key contributor to increased borrowing and reasonable terms or conditions on financing. This indicated increased growth and development of the bank such that it could invest massively in foreign markets (Strange et al., 2013). China’s productivity gains and rapid economic and trade growth have been fueled by FDIs and favourable interest rates.

In 2010, 445,244 foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) were recorded in China, employing 55.2 million people, or 15.9% of the country’s urban workforce. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) reported that China has become a both a major recipient of global FDI as well as a major provider of FDI outflows. China’s FDI inflows in 2018 were $139 billion, making it the world’s second-largest recipient of FDI after the United States. China’s FDI outflows have grew rapidly after 2005 and exceeded FDI inflows for the first time in 2015. China’s FDI outflows reached a historic peak of $196.1 billion in 2016, but declined in 2017 and 2018, reflecting a crackdown by the Chinese government on investment deemed wasteful and well as greater scrutiny by foreign governments of China’s efforts to obtain advanced technology firms and other strategic assets (UNCTAD).

Over the years, assessments of project financial feasibility, risk-return profiles on investments, other commercial factors, and borrowers’ debt limits have drawn international criticism and prompted Chinese authorities to reconsider their policies (Huang et al., 2013).. In the Chinese economy’s push to minimize debt funding, government expenditure was scrutinized. By exporting Chinese know-how, machinery, and equipment, the BRI ventures enhanced economic growth while also preventing the downsizing of some industries (Shaukat, Zhu, and Khan, 2019). Unfortunately, it was part of a debt-financed economy in which Chinese policy and commercial banks bore the credit risk, as well as other risks.

China has always obtained more funds from abroad than it has sent abroad. This was due to Chinese commercial banks borrowing on the international interbank market and foreign-owned banks based in China borrowing from their head offices. Interbank funds account for about half of all cross-border claims and liabilities (Ding, Fung, and Jia, 2015). There is no breakdown of interbank financing, which would demonstrate the value of head office funding. When it comes to cross-border banking by Chinese-owned banks around the world, the image shifts once again.

The CDB and the CMXB established a number of funds to help start, prepare, acquire, finance, develop, and possibly run the projects around the world, especially in regions that China considers strategic to its economic development. The China Eurasia Economic Cooperation Fund, which is led by the CMXB and includes the participation of the BOC, is another example that highlight the implication of financial reforms on large and medium sized financial institutions. China-ASEAN regional cooperation, China-Latin cooperation, China-Arab cooperation, and China-African cooperation are among the other funds that have been facilitated by China’s commercial banks (Li, and Liu, 2019). The Silk Road Fund, the State Administration for Foreign Exchange, and Buttonwood are all sovereign wealth funds that have contributed to FDIs (Gang, 2018). The way projects were treated, whether they were limited to one country or several countries, such as economic corridors, was multinational.

The theoretical argument of this section is Chinese commercial banks have been pillar in financing FDIs. Favorable interest rates that commercial banks offer to the financial market have contributed to domestic and foreign investment. On a global scale, China based commercial banks have funded projects across many sectors, including infrastructure, manufacturing, agriculture and energy (Morris, Parks, and Gardner, 2020). The project management’s design applied by the commercial banks in conjunction with construction and infrastructure companies only added to this impression that commercial banks had accumulated enough funds domestically to support increased domestic and foreign investment (Huang et al., 2013).

Chapter 5

Conclusion

An examination on the impact of interest rate marketization on large, small and rural commercial banks has been provided. As indicated in the empirical, commercial banks were positively impacted by the reforms introduced in the financial sector. The Chinese government steadily lowered the entry barrier to the banking sector and facilitated the establishment and growth of non-state-owned banks and financial institutions, resulting in significant changes in the banking sector’s structure. In addition to regulating the interest rate themselves, the role of government in manipulating interest rate has since been removed, bringing more autonomous in the financial sector. Due to interest rate marketization, China has witnessed rapid economic growth and development over the years making it to be ranked as the fastest sustainable economic growth in man’s history according to WTO.

The stability of China’s economy has been and still remains dependent on the pace of progress that would be made in these areas. Globally, the reforms have allowed the world economy to progress as China continuous to invest in various sectors. This has been seen as China creating a roadmap for its future economic needs. China has been facilitating foreign trade system reform since the reform and opening up by introducing a foreign exchange retention system, creating a foreign exchange swap market later, and easing restrictions on individual foreign exchange use, resulting in the coexistence of official and market-based exchange rates. Chinese banks are already well-known and successful abroad, with their affiliates providing nearly half of their cross-border lending. Their lending now extends beyond traditional trade finance. As a result, they have gained valuable experience that they can apply to funding projects in the BRI’s second phase. Investable and bankable ventures characterize the role of commercial banks and their effort to gain more wealth through financing projects around the world, especially in regions that China has some interest. In contrast to the previous government-to-government financing model, programs should be proposed and implemented by host countries, with funding from both public and private sources. Chinese banks can have a variety of private financing instruments and should collaborate further with other states to ensure that economic growth recorded in China has been transferred to other regions of the world. Because of China’s success in its financial sector, countries around the world, particularly the developing and underdeveloped nations have admired and adopted reforms applied in China. China’s influence is evident in Africa, Asia, and Pacific, and Australia. Financial reforms implemented by China have been applied in these regions, contributing to improved financial performance. While the reforms have also faced constraints in some of the regions, especially because of unstable central government, it is worthwhile mentioning that market-oriented interest rates have been effective in funding SMEs in developing and underdeveloped countries. In other words, China’s market-oriented financial reforms have been applied in other countries to improve financial positions and fund more domestic projects and businesses.

Pricing of loan and deposit services should take into account all of the factors that influence fund pricing, and the net interest margin should be sufficient to cover the cost and target rate of return on capital, as determined by the risk and return to match principle and the interest rate pricing model. Also, banks should use statistical analysis software to determine the risk premium and interest rate pricing model. Loan growth goals dominate credit risk strategies. Commercial bank credit is used for a variety of purposes. Other tools, such as direct fiscal spending, can be used to replace policy targets. Government lending programs and policy bank rationalization Risk management in banks and Supervisory evaluations place too much emphasis on backward-looking variables and not enough on forward-looking variables. Credit risk evaluations that are made in the future. The concentration of bank exposure to state-owned enterprises managed businesses, assured profit margins, and a limited ability to and desire to distinguish Loan rates, as well as tacit guidance on credit flows, stifle the growth of the economy.

References

Bayoumi, T., Tong, H., & Wei, S. J. (2012). The Chinese corporate savings puzzle: a firm-level cross-country perspective. In Capitalizing China (pp. 283-308). University of Chicago Press.

Bell, S. (2013). The Rise of the People’s Bank of China. Harvard University Press.

Boyreau-Debray, G., & Wei, S. J. (2005). Pitfalls of a state-dominated financial system: The case of China (No. w11214). national bureau of Economic research.

China Banking Regulatory Commission. (2017). China Banking Regulatory Commission 2016 annual report.

Chang, M., Jang, H. B., Li, Y. M., & Kim, D. (2017). The relationship between the efficiency, service quality and customer satisfaction for state-owned commercial banks in China. Sustainability, 9(12), 2163.

Chen, Z., Poncet, S., & Xiong, R. (2020). Local financial development and constraints on domestic private-firm exports: Evidence from city commercial banks in China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 48(1), 56-75.

China’s monetary policy and its transmission mechanisms before and after the financial tsunami. Chinese Economy, 44(3), 84–108.

Cui, X. (2016). The impact of interest rate marketization on China’s commercial banks and its tactics. Journal of Mathematical Finance, 6(05), 921. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/310814551_The_Impact_of_Interest_Rate_Marketization_on_China’s_Commercial_Banks_and_Its_Tactics [Accessed March 6, 2021]

Chi, Q., & Fu, S. (2016). The impact of the interest rate liberalization on both banks and small firms: evidence from China. Research in World Economy, 7(2), 26-33.

Clark, G. L., & Monk, A. H. (2011). The Political Economy of US—China Trade and Investment: The Role of the China Investment Corporation. Competition & Change, 15(2), 97-115.

Ding, N., Fung, H. G., & Jia, J. (2015). What drives cost efficiency of banks in China?. China & World Economy, 23(2), 61-83.

Dong, Y., Firth, M., Hou, W., & Yang, W. (2016). Evaluating the performance of Chinese commercial banks: A comparative analysis of different types of banks. European Journal of Operational Research, 252(1), 280-295.

Dornan, M., & Brant, P. (2014). Chinese Assistance in the Pacific: Agency, Effectiveness and the Role of Pacific Island Governments. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 1(2), 349-363.

Friedman, M. (2006). Hong Kong Wrong. Wall Street Journal, 6.

Fungacova, Z., & Weill, L. (2014). Understanding financial inclusion in China. BOFIT Discussion Papers, 2014(10), 1.

Funke, M., & Tsang, A. (2021). The Direction and Intensity of China’s Monetary Policy: A Dynamic Factor Modelling Approach. Economic Record, 97(316), 100-122.

Gang, Y. (2018). Deepen reform and opening-up comprehensively. Create new prospects for financial sector. Bis.org. Retrieved 18 May 2021, from https://www.bis.org/review/r181220h.pdf.

García Herrero, A., & Santabárbara García, D. (2004). Where is the Chinese Banking System Going with the Ongoing Reform?. Documentos ocasionales/Banco de España, 0406.

Geng, Z., Grivoyannis, E., Zhang, S. and He, Y., 2016. The effects of the interest rates on bank risk in China: a panel data regression approach. International Journal of Engineering Business Management, 8, p.1847979016662617.

Guan, F., Liu, C., Xie, F., & Chen, H. (2019). Evaluation of the competitiveness of China’s commercial banks based on the G-CAMELS evaluation system. Sustainability, 11(6), 1791.

Herr, H., & Priewe, J. (1999). High growth in China—Transition without a transition crisis?. Intereconomics, 34(6), 303-316.

Hill, L. E. (1964). On Laissez-Faire Capitalism and’Liberalism’. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 23(4), 393-396.

Hou, X., Wang, Q., & Zhang, Q. (2014). Market structure, risk taking, and the efficiency of Chinese commercial banks. Emerging Markets Review, 20, 75-88.

Hua-yu, S. U. N. (2006). The Effects and Autonomy of Monetary Policy in China from 1994 to 2004 [J]. Contemporary Finance & Economics, 7.

Huang, Y., Wang, X., Wang, B., & Lin, N. (2013). Financial reform in China: Progresses and challenges. The Ongoing Financial Development of China, Japan, and Korea.

Kumari, R., & Sharma, A. K. (2017). Determinants of foreign direct investment in developing countries: a panel data study. International Journal of Emerging Markets.

Korniyenko, Y., & Sakatsume, T. (2009). Chinese investment in the transition countries (No. 107).

Kumiko, O. (2007). Banking System Reform in China: The Challenges of Moving Toward a Market-Oriented Economy. Rand National Security Research Division.

Indicators. (2021). Retrieved 7 June 2021, from https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/china/bank-lending-rate.

Li, C., 2014. China’s Interest Rate Liberalization Reform. [online] Frbsf.org. Available at: <https://www.frbsf.org/banking/files/Asia-Focus-China-Interest-Rate-Liberalization.pdf> [Accessed 26 April 2021].

Li, J., & Liu, M. H. (2019). Interest rate liberalization and pass-through of monetary policy rate to bank lending rates in China. Frontiers of Business Research in China, 13(1), 8.

Li, N. (2019). Impact of Tax Factors on Chinese FDIs. In China’s International Investment Strategy (pp. 56-66). Oxford University Press.

Liang, T., 2017, July. Research on Interest Rate Marketization and Risk Control of Commercial Banks. In 2017 3rd International Conference on Economics, Social Science, Arts, Education and Management Engineering (ESSAEME 2017). Atlantis Press.

Liu, K. (2018). Why does the negotiable certificate of deposit matter for Chinese banking?. Economic Affairs, 38(1), 96-105.

Liu, X., Sun, J., Yang, F., & Wu, J. (2020). How ownership structure affects bank deposits and loan efficiencies: an empirical analysis of Chinese commercial banks. Annals of Operations Research, 290(1), 983-1008.

Kim, M., & Xin, D. (2021). Export Spillover from Foreign Direct Investment in China During Pre-and Post-WTO Accession. Journal of Asian Economics, 101337.

Ma, X., Wang, F., Chen, J., & Zhang, Y. (2018). The income gap between urban and rural residents in China: since 1978. Computational Economics, 52(4), 1153-1174.

Machobani, D., Boako, G., & Alagidede, P. (2017). Uncovered Interest Parity, Purchasing Power Parity and the Fisher effect: Evidence from South Africa. Frontiers in Finance & Economics, 14(2).

Meng, T., Sun, M., Zhao, Y., & Zhu, B. (2020). Analysis of the Impact of Interest Rate Liberalization on Financial Services Management in Chinese Commercial Banks. Scientific Programming, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.hindawi.com/journals/sp/2020/8860076/ [Accessed March 7, 2021]

Morris, S., Parks, B., & Gardner, A. (2020). Chinese and World Bank Lending Terms: A Systematic Comparison Across 157 Countries and 15 Years. Center for Global Development.

Morrison, W. M. (2019). China’s economic rise: History, trends, challenges, and implications for the United States. Current Politics and Economics of Northern and Western Asia, 28(2/3), 189-242.

Okazaki, K. (2017). Banking system reform in China: The challenges to improving its efficiency in serving the real economy. Asian Economic Policy Review, 12(2), 303-320.

People’s Republic of China | Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2020 : An OECD Scoreboard | OECD iLibrary. (2020). Retrieved 22 June 2021, from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/31f5c0a1-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/31f5c0a1-en

Quintyn, M. G., Laurens, B. J., Mehran, H., & Nordman, T. (1996). IX The Agenda for Developing a Market-Based Monetary and Exchange System. In Monetary and Exchange System Reforms in China. International Monetary Fund.

Rolland, N. (2017). China’s “Belt and Road Initiative”: Underwhelming or game-changer?. The Washington Quarterly, 40(1), 127-142.

Roubini, N., & Sala-i-Martin, X. (1992). Financial repression and economic growth. Journal of development economics, 39(1), 5-30.

Shaukat, B., Zhu, Q., & Khan, M. I. (2019). Real interest rate and economic growth: A statistical exploration for transitory economies. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, 534, 122193.

Shevlin, A., & Wu, L. (2014). China: The path to interest rate liberalization. Liquidity Insights. Retrieved from https://am.jpmorgan.com/blob-gim/1383216432861/83456/WP-GL-China-The-path-to-interest-rate-liberalization.pdf [Accessed March 6, 2012]

Stiglitz, J. E. (2009). The anatomy of a murder: Who killed America’s economy?. Critical Review, 21(2-3), 329-339.

Strange, A., Park, B., Tierney, M. J., Fuchs, A., Dreher, A., & Ramachandran, V. (2013). China’s development finance to Africa: A media-based approach to data collection. Center for Global Development Working Paper, (323).

Tan, Y., Ji, Y., & Huang, Y. (2016). Completing China’s interest rate liberalization. China & World Economy, 24(2), 1-22.

The People’s Bank of China, China Financial Institute (2019), “Almanac of China’s Finance and Banking in 2018”, Beijing: China’s Finance and banking Almanac Press.

Tymoigne, E. (2006). Fisher’s Theory of Interest Rates and the Notion of’Real’: A Critique.

Warue, B. N., Charles, B. J. M., & Mwania, P. M. Theories in Finance Discipline: A Critique of Literature Review.

WATKINS, D., LAI, R., & BRADSHER, K. (2018). The World, Built by China. Nytimes.com. Retrieved 16 May 2021, from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/11/18/world/asia/world-built-by-china.html.

Wu, H. X. (2007). The Chinese GDP growth rate puzzle: How fast has the Chinese economy grown?. Asian Economic Papers, 6(1), 1-23.